|

==============================================================================

TOPIC: Shenandoah National Park

http://groups.google.com/group/entstrees/browse_thread/thread/b55b8716e1dbeb16?hl=en

==============================================================================

== 1 of 2 ==

Date: Wed, Mar 26 2008 4:02 pm

From: "Edward Frank"

ENTS,

With many people going to western North Carolina in a few weeks, I

thought I would revisit a trip to Shenandoah National Park and

environs from a couple years ago.

Ed Frank

Shenandoah National Park, VA, July 2005

July 05, 2005 The day started and ended with the sound of thunder. I

awakened at around 6:30 to the sound of rolling thunder through my

drapes. It was my last night for a long time in my own bed, but I

did not sleep well from the anticipation of my southward journey.

After a a few delays I got up and packed the last items for my trip

- razor, tooth brush, alarm clock. The I was off, I headed down 219.

219 runs south and is a mixture of small windy back roads to

four-lane thoroughfares. I opted to not stop at any of the familiar

parks along the way - the Portage Railroad National Historic Site,

nor the Johnstown Flood National Memorial, but to head on down to

Maryland. These were familiar paths for me as I went on caving trips

and visited the sites in West Virginia and western Virginia many

times in the past. Just after entering Maryland I headed east on

68/40.

The first stop was Sideling Hill Exhibit Center. http://www.mgs.md.gov/esic/brochures/sideling.html

The Exhibit Center is located beside a deep road cut slicing through

the axis of of a sharply folded syncline. I stopped on the south

side of the east-west parkway. From here it is a short walk up to a

pedestrian overpass. The best view of the syncline is from the south

end of the overpass looking to the north side of the fold. The

overpass leads to a three story exhibit center on the north side of

the road. In the exhibit center are many displays explaining the

geology of the area and information on the nearby wildlife area.

Also on the north side is a viewing platform atop a series of

stairs. The view from the platform shows you the south face of the

road cut and an oblique view of the north face. It is certainly a

worthwhile stop to stretch your legs. I don't think it is

destination in its own right unless you are going on a geology field

trip. Wikipedia describes the site as follows: "The Sideling

Hill road cut is a 340-foot deep road cut where Interstate 68 cuts

through Sideling Hill, about 6 miles west of Hancock in Washington

County, Maryland. It is notable as an impressive man-made mountain

pass, visible from miles away and is considered one of the best rock

exposures in Maryland and the entire northeastern United States.

Almost 810 feet of strata in a tightly folded syncline are exposed

in this road cut. Although other exposures may surpass Sideling Hill

in either thickness of exposed strata or in quality of geologic

structure, few can equal its combination of both. There is an

Exhibit Center to help provide the public with a better

understanding of the geology of the cut. A pedestrian walkway bridge

crosses I-68 for better access to the cut, along with a picnic area

and rest area facilities." http://www.dnr.state.md.us/publiclands/western/sidelinghill.html

Certainly as the exhibit sits astride an major interstate, this is

one of the most visited state parks in the country. The exhibit sits

on the edge of the Sideling Hill Wildlife Management Area, a

3,000-acres of mixed oak-hickory forest that straddles Sideling Hill

Creek.

Shortly after this I turned south on 522 at Hancock,Maryland toward

Winchester VA http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Winchester

_Virginia A

beautiful doe with a couple of fawns were grazing across a small

swampy pond just to the side of the interstate. 522 first passes

into West Virginia just a few miles from Berkley Springs. One thing

that really caught my eye were the patches of cheery orange tiger

lilies growing in patches along the road. Winchester is a modest

town in Virginia. There are a series of giant artificial apples

scatter across the town painted with scenes. I believe they have an

annual apple blossom festival. It is a confusing town to drive

through - many one way streets and the routs are not well marked, or

when they are they form a cluster of six or seven signs each

pointing to different routes in different directions. From here to

Front Royal, VA the northern end of Shenandoah National Park.

Just before reaching the park I was driving down the road and

suddenly I saw some large dinosaurs along the road. These concrete

dinosaurs were advertising a roadside attraction called dinosaur

world. I stopped and took a few photos but did not take the tour.

Giant dinosaurs, I just had to stop. I ask the girl at the

convenience store if she had noticed there were dinosaurs outside.

Yes she had. She told me there had been quite a few comments made

when the dinosaurs were last restored and painted bright colors

rather than the gray they had been painted previously. On to

Shenandoah.

Shenandoah National Park runs along the spine of a ridge running

south-southwest for a distance of about 100 miles. http://www.nps.gov/PWR/customcf/apps/maps/showmap.cfm?alphacode=shen&parkname=Shenandoah%20National%20Park

The road continues southward as the Skyline Drive (including the

park). My first memories of visiting the Skyline Drive was riding in

the car as my father drove along the highway in a dense fog. We

could not see the lines the edge of the road because of the fog

thickness.. I entered the park through the Front Royale entrance at

the north end of the park.

A couple of miles into the park I found some unusual wildflowers

with tall spiky white flowers - black snakeroot- and stopped for a

few pictures. There are large numbers of overlooks along the

highway, averaging over one per mile within the park. These may face

westward or eastward overlooking the valleys below as the road winds

from one side of the narrow ridge to the other. It is interesting to

see how the weather may be sunny on one side of the ridge, while on

the other it may be pouring down rain. I stopped at the Dickey Ridge

Visitor Center, the northernmost park office before heading to the

Matthews Arm Campground. I did not know what to expect so I decided

to set up camp first then go sightseeing. The campground was

sparsely filled, so I picked out a spot and set up my tent. It is a

steep climb up out of the campground and my little Tracker sputter

and spurted and threatened to die. I figured I had to get some gas

treatment before I returned if I wanted to make it out again.

Five-fingered tuliptree

Upon reaching Skyline Drive again I headed back northward. A short

distance ahead was someone stopped in the road coming the other

direction. A black bear was foraging along the shoulder of the road.

I grabbed my camcorder and started shooting. I probably got two full

minutes of video before the bear wandered off. I continued northward

stopping at various overlooks for views and still photos. Eventually

I found one with a cell phone signal and called home to tell my

mother I was fine. There were many short hikes listed in a booklet I

bought and there was time to squeeze in a couple before dark. The

first was Lands Run, a 1.3 mile round trip to a small waterfall. The

thing about most hikes in the park is that you are starting off at

the ridge top and going downhill to see something, then the hike

back is all uphill. An unusual tree along the trail was a multistem

clump of tulip tree. Five separate stems grew upward, then ant a

height of 15 feet or so they spread outward like the fingers on your

hand.

The park has a long history of logging. The park website http://www.nps.gov/shen/naturescience/forests.htm

"Surveys in 1940 and the late 1980s show that the forests of

Shenandoah National Park have changed dramatically in 50 years. The

changes include the percentage of forested lands, and the ages,

sizes, and species of trees. In 1940, Shenandoah was a young park.

It was authorized by act of Congress in 1926 and established in

1935. For almost 200 years prior to park establishment people had

harvested and used the resources of these mountains. Timbering,

grazing, hunting, and cultivation ceased when these lands became a

national park. In 1940 the park was 85% forested. The rest of the

park was open ground, including grasslands, cultivated fields, and

old fields reverting to forest. Previously grazed areas were being

occupied by bear oaks and pitch pines. By 1990 the park was 95%

forested. In the more mature forest, bear oak stands had disappeared

and pitch pine numbers had dwindled. In 1940 there were no yellow

poplar stands and cove hardwoods covered only 6% of the area. By

1990, yellow poplar stands covered 16% of the park and cove

hardwoods covered 15%. These forest types grow in moist sites. Their

increase is evidence of more organic matter in the soil and more

adjacent protective forest canopy cover. In 1940 chestnut oaks and

northern red oaks covered 72% of the park. By 1990, their numbers

were down to 59%. Since 1990 repeated defoliation by non-native

gypsy moth caterpillars has contributed to the deaths of even more

oaks."

Black Snakeroot Flowers and Bees

The second hike was to Fort Windham Rocks. It was essentially a

level hike that includes a short segment of the Appalachian Trail.

The trail leads to some rock formations that are metamorphosed

basalt called the Catocin Formation. The outcrop is to the right of

the trail with the main mass of the outcrop forming an exposure

40-50 feet high. On the way back to the Geo I experimented with

taking flash pictures of the bees and other insects madly scurrying

among the plentiful black snakeroot flowers along the trail.

It was getting late so I took off southward again. I was going to

hit highway 211 west out from the park to find some food, gas, and

stuff for my car. There were a few sprinkles, but the sun was

shinning. To the east were fantastic rainbows arching across the

sky. By the time I reached 211 it was looking grayer. A buck deer

horns in velvet was browsing along the off ramp. I stopped and took

some still photos. I wanted to get my camcorder, but I was afraid if

I moved, the deer would flee. I headed westward toward Luray. By the

time I got to the valley bottom, there was a massive dire looking

storm brewing. I picked up the supplies in Luray and headed back. As

I drove northward back towards Matthews Arm Campground it rained so

hard that at time I could barely see the road. But I drove slowly

and pushed onward.

When I arrived back at the campsite, I found one of my tent flaps

had come open. Inside my tent were puddles of water. My sleeping

back was sitting atop a plastic covered foam sleeping pad, so it was

not soaked, but still wet in places. My pillow was damp. I tried to

stretch out in the Tracker, but there was little room. The lightning

flashed and thunder rolled. Lightning bugs were fluttering about in

the trees flashing away. I wonder if they were excited by the

lightning strikes? As the rain paused for a brief respite, I decided

to give my tent a try. I soaked up the water on the floor with a big

towel, spread out the sleeping bag to put the wet spots down, and

got a dry blanket from the truck to cover myself. As I lay in the

somewhat damp bed, the rain began to fall. It is neat to listing to

the raindrops strike the tent walls just inches from your head. I

lay for awhile listening to the patter of raindrops, and I fell to

sleep to the sounds of thunder.

July 6, 2005 I had camped out overnight at the Matthews Arm

campground. I awakened just after 6 am to the dampness. The water

from the previous night had soaked through my belongings and myself.

I broke camp and headed out. My Tracker took the climb back out from

the campsite with no complaint, at least the fuel additive worked.

Overall it wasn't a bad morning. The weather fluctuated from cloudy

threatening to rain to bright sunshine depending on where you were

on the road. I headed south. I must have stopped at almost every

overlook on my way to Big Meadows.

Mary;s Rock Tunnel

There is a 600 foot tunnel through the hill at Mary's Rock built in

1932. The mountain laurel is pretty much past its peak here at the

park, but isolated bushes are still in bloom. One hike I wanted to

try was to Stony Man Peak. At the peak are remnant populations of

balsam fir and red spruce dating from a time when the climate was

much colder here. But the weather looked bad, it was sprinkling on

and off, I decided to try this hike another day. The Appalachian

trail runs from Georgia all the way to Maine. The Trail runs through

the park parallel to skyline drive frequently cross crossing the

highway. Occasional long distance hikers could be spotted as I made

my way southward along the drive. Within the park are almost 500

miles of trail, so anyone looking for a place for hiking, there is

plenty of opportunity in the park.

One thing that had caught my attention were the many standing dead

trees in the park. There were both deciduous and conifers. The

conifers were generally hemlocks. In 2005 I wrote the following:

"These great trees had been killed in the past couple seasons

by the Hemlock Wooly Adelgid an invasive pest that arrived in this

country from Japan It has been decimating the hemlock populations

throughout the south. Hemlock occupies a unique niche in the

ecosystem of these forests, I am not sure if there will be anything

that can really replace it if all of the hemlocks die off. This may

be the beginning of a major blight like killed the American Chestnut

earlier in this century. The adelgid does not seem to have been as

effective in the north yet. Whether this is because of the freezing

winters, or just that it hasn't traveled that far. There has been

some success in the south using chemical pesticides to inoculate the

trees and with release of predatory beetles, but these processes are

slow and expensive and cannot practically save the vast tracks of

forest affected by the pest."

In response to my HWA/Hemlock survey the Park Service wrote (2007):

"The forests of Shenandoah National Park occur primarily on

steep rocky slopes. Higher elevation forests of the park are

dominated by chestnut oak, red oak, hickory, and mountain laurel.

Mixed hardwood forests of ash, cherry, basswood, birch, red oak, and

maples cover the mid and lower-slopes, and tulip poplar and spice

bush dominate the lowest slopes and stream valleys. Eastern Hemlock

areas comprise approximately 250 acres (mostly which are currently

being treated with imidacloprid soil injections). Human disturbance

occurred in many park locations prior to 1935. Since then, there has

been very little (e.g. trail maintenance) or no disturbance. The

last old-growth hemlock stands succumbed to the HWA from 1995-2003

(Camp Hoover, Hemlock Springs, and Limberlost - in that order). In

general, the lower elevation hemlock sites (1000'-2000') became

infested and declined quicker than the higher elevation sites

(3000'-4000'). Over the last 11 years, several droughts are believed

to have accelerated HWA-related hemlock mortality throughout the

park (e.g. two droughts between 2000 and 2002 were probable causes

of the previously healthy Limberlost old-growth (high elevation)

stand for having quickly succumbed to the HWA during 2001-2003).

Hemlocks found farther away from park streams have been more

susceptible to drought than ones growing near the stream edge or in

moister areas. The lack of sustained cold winters/springs from

1993-2006 also hastened hemlock decline and mortality in many areas.

Early on, resource managers at Shenandoah weren't sure what the

long-term effects would be. They also didn't know what HWA

treatments worked well in the early 1990s. Our techniques, access,

and budget were limited, and bio-controls weren't realistically

available. In 2006, HWA Suppression took place on 157 acres

throughout the park. Imidacloprid soil injections were made on 97

acres (550 trees). These injections are made every other year. M-PedeR

insecticidal soap was applied on 60 acres (or 510 trees) that were

treated one-two times during the year. in general, hemlock crown

health remained stable in 2006 in treated areas. Moisture conditions

were sufficient throughout the growing season and drought was not a

crown health decline factor." The dead deciduous trees were

generally killed by another introduced invasive pest, the Gypsy

Moth. The gypsy moth is not as selective in its diet and will feed

on almost any species of tree. However it does have some preferences

and the oaks are the hardest hit by the moth caterpillars. Many of

the standing deciduous trees were oaks. There had been some fires in

certain areas of the park, but these dead specimens were not a

result of fire. They were scattered about the hillside among other

healthy trees in areas not affected by fire as marked on the park

service maps. A copy of an article from the parks newsletter

Resource Management Newsletter 21 from 2005 discussing the HWA is

appended at the end of this document.

In the Skyland section of the park, near the horse stables, I had

the opportunity to take some video of a doe and two spotted fawns

feeding next to the road. When first established the park did not

have any whitetail deer living in the park area. They had been

hunted until gone from the area by previous generations. Whitetail

deer were reintroduced in the park in the 1930's after the

establishment of the national park. Today the park supports a good

population of healthy deer. Other animals absent from the area or

rare are now making a comeback. In 1976 the US Congress 40% of the

park as wilderness, partially because of the comeback the vegetation

and wildlife has made since the park's establishment. Most of the

area designated wilderness can only be seen on longer hikes or

through hikes on the Appalachian trail.

Dark Hollow Falls

One short hike I could not pass up was the trail to Dark Hollow

Falls. The sign said a 1.4 mile round trip hike to an 80 foot

waterfall. The weather had cleared so off I went. The entire trip to

the falls is downhill. There is an elevation drop of 440 feet. Soon

I reached to the top of the falls, a small stream tumbling off a

rock ledge. Access to the top of the falls itself is blocked by

fencing, but the path continues down another 0.2 miles to the base

of the falls itself. It had rained so a fair amount of water was

tumbling its way down the cliff side in several stair-steps

segments. Several groups had made their way to the base of the

falls, and some were passed heading back out. This is the closest

waterfall to Skyline drive in the park and was worth the hike down

and back out again. Along the trail are the small items that seem to

catch my eye whenever I hike. One log was covered with pale

blue-green foliose lichens. Under a laurel bush was a pile of

mountain laurel flowers lying on the moss. It is these details that

make many of these hikes memorable, not just the major features you

go to see.

Next stop was the laundromat at Big Meadows. I needed to dry out my

sleeping bag, blanket, and pillows. It took awhile but gave me an

opportunity to catch up with my writing. From here I headed south

again stopping at numerous overlooks. At the Blackrock overlook, a

trail leads to a talus slope on the hillside. I stopped at a dozen

more overlooks along the way, but eventually exited the park at

Rockfish Gap and headed east on 64.

The park service website has a couple of unusual sections that I

wanted to mention. The first deals with natural soundscapes: http://www.nps.gov/shen/naturescience/naturalsounds.htm

"Soundscapes are important natural features of national parks.

Besides contributing to the visitor experience they may be

indicative of natural resource conditions. Wildlife may use

particular sounds during courtship and mating or other behaviors

which all make up the acoustic ecology of the area. Sudden sounds

stem from trees or branches falling or when rock slides occur.

Burning leaves and wood give off crackling and hissing sounds.

Natural sounds may also be indicative of a given season. For

instance, the songs and calls of birds may only be present during

spring or fall migrations indicating their transient presence.

The soundscapes of parks should be valued by visitors. Most visitors

live in locations where they do not experience the sounds of natural

settings. Instead, their soundscapes are dominated by the sounds of

human activity - motor vehicle traffic, airplane traffic, sirens of

emergency vehicles, construction equipment operation, and so forth.

Even in park settings, these sounds."

The second dealt with natural odors: http://www.nps.gov/shen/naturescience/natural_odors.htm

"How often have you walked through the woods and smelled the

aroma of pine trees or the musty odor of damp soil and humus?

Perhaps you have smelled the sweet fragrance of wild rose or white

violet or been offended by the pungent odor of a skunk. These and

many other natural odors, whether we realize it at first or not,

constitute an important element of experiencing Shenandoah National

Park. Natural odors also play key roles in the interactions of

wildlife with one another and their habitats. Mates are found or

rejected by odor, predator and prey interactions are partially

determined by odor, and locations for nests, dens, and hives may be

located in part by odor. Our lives are often dominated by odors that

people generate - perfume, room fresheners, cooking food, automotive

emissions, livestock and poultry odors, chemical disinfectants and

sanitizers. We live and work in climate controlled environments

where the air we breathe may be filtered. Perhaps we have lost our

familiarity with the odors found in a natural setting. Exploring

Shenandoah National Park is a place where you can experience those

natural odors. A visitor might encounter the following odors

associated with plants at Shenandoah. The scratched twigs of black

birch (Betula lenta) and yellow birch (Betula allegheniensis) smell

like wintergreen. The roots of sassafrass (Sasafrass albidum) smell

like rootbeer and the crushed leaves of sweet cicely (Osmorhiza

claytonia) give off the scent of licorice. Along with the pleasing,

comes the unpleasant. Scratched or broken twigs of wild cherry (Prunus

serotina) smell like bitter almond, an odor produced by the cyanide

in the bark. Crushed false hellebore (Veratrum viride) and skunk

cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus) both smell like skunks. Perhaps most

offensive of all are the dark purple flowers of wild ginger (Asarum

canadense) which smell like rotting flesh."

I found it interesting that the park chose to emphasize these

aspects of a visit to the park, as they seem to be rarely mentioned

in similar context.

Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Update

By Mary Willeford Bair

Resource Management Newsletter 21

Hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae) continues to threaten

hemlocks in Shenandoah National Park. First discovered in the park

during the fall of 1988, they are now wide-spread throughout. Few

hemlocks have escaped colonization by this serious forest pest.

Heavy infestations of hemlock woolly adelgid on eastern hemlock

trees have progressively led to crown health decline and tree

mortality which threatens to eliminate all eastern hemlock stands in

Shenandoah National Park. In 1990, park staff established

six monitoring sites within hemlock areas in accordance with

established protocols for forest vegetation monitoring (Smith and

Tolbert, 1990) under the auspices of the park's Long Ecological

Monitoring Program. Locations of sites are Thornton River in the

north district; Pass Run, Whiteoak Canyon, Limberlost, Rapidan Camp

in the central district;

and North Moorman's River in the south district. Crown health data

collected in recent years was compared to baseline data collected

the first year. The percentage of dead trees within monitored stands

has significantly increased.

RESULTS

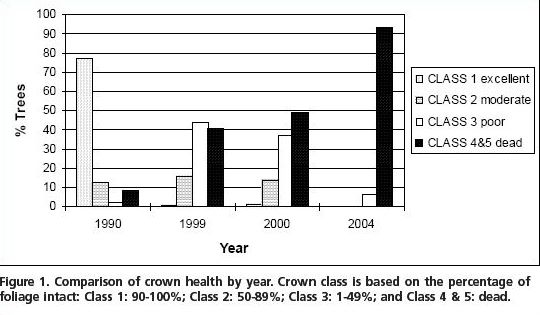

Comparisons between tree crown health data from 1990/1991 to 2004

show a dramatic shift of trees exhibiting excellent crown health

(crowns with 90-100% foliage intact)

to ones exhibiting poor crown health (1-49% foliage intact) or that

are dead. By 2004, adelgid-attributed mortality had increased from

an initial 8% to 93%. Additionally, moderate-poor canopies comprised

less than 10% and excellent canopies were nonexistent in 2004.

DISCUSSION

Although the small sample size and the site selection technique do

not allow us to draw comprehensive conclusions about park wide

hemlock health, data from the sites provide a

snapshot of crown health in dense, untreated hemlock stands. A

revised sampling scheme was implemented in 1999. This new sampling

design allows conclusions to be drawn about hemlock crown health on

a park wide basis but the data has yet to be analyzed. Despite this

lack of analysis, it is clear that hemlock woolly adelgid has caused

significant decline in hemlock crown health and tree mortality has

increased park wide.

Without intervention, there is a very real possibility that this

insect pest could directly or indirectly eliminate eastern hemlocks

from Shenandoah's ecosystem. Efforts to extend the lives of our

remaining healthy hemlocks continue. Adelgid suppression in 2005

will be accomplished through insecticidal soap spraying and by soil

treatments of MeritR. The systemic pesticide MeritR (Imidacloprid)

remains at effective levels to adelgids for over a year. The battle

to save a lasting remnant of Shenandoah's hemlock gene pool for

future generations continues.

References

Smith, D.W., and J.L. Tolbert. 1990. Shenandoah National Park

Long-Term Ecological Monitoring System, Section II, Forest Component

User Manual, 1st Edition. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State

University, Blacksburg, VA. (with revisions by Wendy Cass, 1999).

Mary Willeford Bair is a Biological Science Technician.

== 2 of 2 ==

Date: Wed, Mar 26 2008 6:00 pm

From: James Parton

Ed,

Now this looks familiar. Very similar to here in western North

Carolina which I call home. I have never ventured far enough north

on

the Parkway to reach Shenandoah National Park but I have plans to.

Nice Post!

James P.

=============================================================================

TOPIC: Shenandoah National Park

http://groups.google.com/group/entstrees/browse_thread/thread/b55b8716e1dbeb16?hl=en

==============================================================================

== 1 of 2 ==

Date: Thurs, Mar 27 2008 9:35 pm

From: JamesRobertSmith

I dislike visiting Shenandoah National Park for a number of reasons.

To me, it is the most ecologically sick national park I have ever

visited. The forest is very sick because of a number of reasons, not

least of which are the invasive species. Another huge problem is the

urban sprawl that has crept right up to the eastern borders of the

park making it not much better than a city park. I always get

depressed when I visit Shenandoah and I'm not sure I'll ever go back

there.

== 2 of 2 ==

Date: Thurs, Mar 27 2008 9:54 pm

From: "Edward Frank"

Bob,

The park is heavily impacted to be sure, but on the other hand it

has made a good come back from 80 years ago. "when park was

established in 1935, logging, farming, grazing, and the chestnut

blight had rendered one third of the park completely deforested, and

the remaining land covered with brush and a very young regenerating

forest." I have not seen all of the park, so I am not ready to

abandon it yet. The park website says "Shenandoah National Park

has 431 rare plant populations representing 66 rare plant species.

The highest concentration of these is in the park's Big Meadows

area." There are some areas of the park in particular I want to

explore. One area is called the "Old Rag" and represents a

granitic core of the mountains with a number of pockets of old

growth - stunted, but still old growth. So I will be back, likely in

a few weeks.

Ed

==============================================================================

TOPIC: Shenandoah National Park

http://groups.google.com/group/entstrees/browse_thread/thread/b55b8716e1dbeb16?hl=en

==============================================================================

== 1 of 2 ==

Date: Fri, Mar 28 2008 4:45 pm

From: JamesRobertSmith

Old Rag is a great section. Be prepared from some serious rock

scrambling! It's one of the most spectacular spots in the park.

Last time I was there my visit made me exceedingly depressed. The

park

had just experienced a controlled burn that got way out of control

when some high winds appeared out of nowhere, severely scorching

quite

a swath of forest. The gypsy moth was killing like crazy. There were

no living hemlocks anywhere. Suburban developments were creeping up

all around the eastern side of the park and the northern entrance

was

like a big city traffic jam. At least when the park was formed you

had

vast rural areas to the east, even if the timber was largely gone.

Also, it was in May and we camped at Big Meadows and a freakish cold

front came through. The winds tore at our tents the whole time,

wrecking our cooking shelter. In addition it rained and the

temperatures never ventured much above 40. It was a pretty miserable

trip.

Some other good hikes are Stony Man and Little Stony Man. The old

growth hemlock groves are all dead, although it might still be

interesting to examine the rotting snags.

==============================================================================

TOPIC: Shenandoah Hemlocks

http://groups.google.com/group/entstrees/browse_thread/thread/bdae799579bb68df?hl=en

==============================================================================

== 1 of 1 ==

Date: Fri, Mar 28 2008 8:02 pm

From: "Edward Frank"

Neil Will, Bob Smith, ENTS,

I am wondering what information we have on the hemlocks at

Shenandoah National Park?

I reported a few days ago some information from the NPS "Eastern

Hemlock areas comprise approximately 250 acres (mostly which are

currently being treated with imidacloprid soil injections). Human

disturbance occurred in many park locations prior to 1935. Since

then, there has been very little (e.g. trail maintenance) or no

disturbance. The last old-growth hemlock stands succumbed to the HWA

from 1995-2003 (Camp Hoover, Hemlock Springs, and Limberlost - in

that order). In general, the lower elevation hemlock sites

(1000'-2000') became infested and declined quicker than the higher

elevation sites (3000'-4000'). Over the last 11 years, several

droughts are believed to have accelerated HWA-related hemlock

mortality throughout the park (e.g. two droughts between 2000 and

2002 were probable causes of the previously healthy Limberlost

old-growth (high elevation) stand for having quickly succumbed to

the HWA during 2001-2003). HWA Suppression took place on 157 acres

throughout the park. Imidacloprid soil injections were made on 97

acres (550 trees). These injections are made every other year."

And from a management newsletter in 1995:

Comparisons between tree crown health data

from 1990/1991 to 2004 show a dramatic shift of trees exhibiting

excellent crown health (crowns with 90-100% foliage intact) to ones

exhibiting poor crown health (1-49% foliage intact) or that are

dead. By 2004, adelgid-attributed mortality had increased from an

initial 8% to 93%. Additionally, moderate-poor canopies comprised

less than 10% and excellent canopies were nonexistent in 2004.

I looked on the ITRDB and found one dating sequence for the

Limberlost area of the Park. The data from the COFECHA file reads as

follows:

Detrend method: Linear regression of any slope

Collection purpose: Ecology - insect outbreaks

Data was collected from two sites in SNP. These sites were the Upper

Staunton River area and Limberlost.

Data was gathered to support dissertation research on the impact of

the hemlock woolly adelgid which was first seen in 1988.

The number of cores collected was restricted by Park Service due to

possible impact to trees. The purpose was to see if pre-existing

conditions were present (slow growth) which may have set the stage

for hemlock decline due to adelgids attack. Growth prior to the

adelgid was observed to be very high(compared to past 100 years)and

did not set stage for attack. Trees of all ages were cored for this

study.

COFECHA output:

Chronology file name : VA024.CRN

Measurement file name : VA024.RWL

Date checked : 07APR05

Checked by : H. ADAMS AND J. LUKAS

Beginning year : 1756

Ending year : 1997

Principal investigators: Pat Dougherty

Site name : Shenandoah National Park

Site location : Virginia

Species information : TSCA EASTERN HEMLOCK

Latitude : 3828

Longitude : -07828

Elevation : 975M

There is data from acouple of other sites in Virginia, with two

collections from the Ramsey Draft area of George Washington forest http://www.hikingupward.com/GWNF/RamseysDraft/

west of the Park.

Have any of the hemlock trees in the park been measured, ENTS method

for height? If so what values were obtained? I am wondering of there

is any more agedata fo rthe no dead hemlocks from the Park?

What particular sites of the ones designated as Old growth - Camp

Hoover, Hemlock Springs, and Limberlost - had the largest and or

oldest tees?

Would it be worthwhile at this stage to try to document the standing

dead trees as a datapoint if nothing else?

The NPS reported that they removed some of the dead trees:

The park only removed hazard dead/dying hemlocks in high use

developed areas (e.g. along Skyline Drive, around Limberlost

Accessible trail, high use picnic areas, and popular day use areas

(Camp Hoover). If possible, the hemlock logs and tops were left on

site (Limberlost). In some historic areas (Camp Hoover), the logs

were removed and the branches were chipped. Most of this work was

done by park maintenance/Trails crews except for the highly

technical removal work (which was mostly done by contract).

I am wondering if there are any logs or stumps remaining in these

areas that could be used for ring counts? I have not been there to

see for myself.

Thanks,

Ed Frank

==============================================================================

TOPIC: Shenandoah Hemlocks

http://groups.google.com/group/entstrees/browse_thread/thread/bdae799579bb68df?hl=en

==============================================================================

== 1 of 1 ==

Date: Sun, Mar 30 2008 5:12 am

From: JamesRobertSmith

Thanks for that information!

I hadn't seen any living hemlocks there on my last couple of visits.

It would be good to locate those and see the ones surviving. I was

in

the Limberlost grove when I was much younger. It was an impressive

forest.

Alas.

==============================================================================

TOPIC: Shenandoah National Park

http://groups.google.com/group/entstrees/browse_thread/thread/b55b8716e1dbeb16?hl=en

==============================================================================

== 1 of 1 ==

Date: Mon, Mar 31 2008 8:04 pm

From: "Darian Copiz"

I was just there March 8th on a beautiful day. Driving along Skyline

drive,

much of the landscape was shrouded in mist - so the sprawl to the

east

wasn't visible. The mist was crawling across the ridges and dead

hemlocks

stood out of it like ghosts. At Big Meadows it was raining while I

was

exploring a high elevation seepage swamp - it felt like being in a

different

world. This was followed shortly by warm sun and blue sky while

walking

across the meadow. A couple hours later a thunderstorm passed

through, then

at Hogback Mountain is was snowing. The varied weather, wide variety

of

habitats, high level of plant diversity, and old growth can make for

a very

interesting visit. Individual experiences, of course, can vary, but

I

bought a season pass when I was there.

Darian

==============================================================================

TOPIC: Shenandoah National Park

http://groups.google.com/group/entstrees/browse_thread/thread/b55b8716e1dbeb16?hl=en

==============================================================================

== 1 of 1 ==

Date: Tues, Apr 1 2008 7:39 am

From: JamesRobertSmith

I know the bog you're talking about. It is a very interesting place.

Especially if you go there when there aren't so many people around.

|