WNTS – Trip Report – Western Juniper - Central Sierra Nevada Range

Western juniper is a western species (Juniperus occidentalis) that has two varieties (J. occidentalis var. australis and J. occidentalis var. occidentalis).

Western juniper (var. occidentalis) is

generally distributed throughout the western United States (southeast

Washington to southern California and east to southwestern Idaho), whereas the

variety australis occurs primarily in

upper elevations in the coastal range and Sierra Nevadas of California, with a

lesser presence in Nevada. During the past 150 years,

western juniper, as a species, has extended its range and now occupies

approximately 42 million acres (17 million hectares) in the Intermountain West

(Bunting 1990). It is thought that the cessation of seasonal burning by Native

Americans, and later, the introduction of cattle grazing have influenced this

extension of range. The role of climate change isn’t fully understood, but

can’t be discarded. Much of the west in

the early 1900’s recorded higher than usual temperature and precipitation

regimes, which positively influenced many forest species’ introduction and

growth.

In

historic times, western juniper was used for “firewood, charcoal, corrals,

poles, and fence posts (Dealy, et al 1978). Extremely durable and rot

resistant, western juniper wood splits easily, burns clean and produces little

ash (Herbst, et al 1978). Western juniper woodlands can produce 8 to 11 cords

of firewood per acre. It is however estimated that 7 hours of labor are

required per cord to cut, limb, pile slash, and gather the wood, somewhat

negating its net value to landowners (Budy 1984). Adding insult to injury, more

so than most species, western juniper in most of its locations is known to dull

saws since wind-blown sand particles readily adhere to

its shaggy bark (Herbst 1978).

In

more recent times, commercial uses include paneling, interior studs,

particleboard, veneer, and plywood, but each require slow and careful kiln

drying to prevent warping (Herbst 1978). The essential oils of western juniper

are used for flavoring or scenting agents in medicines, beverages, condiments,

aerosols, insecticides, soaps, and men's cosmetics (Herbst 1978). The

cone-berries of western juniper are edible and taste best when dried (Herbst

1978). Western juniper foliage has been added to chicken feed to produce

gin-flavored eggs for human consumption (Herbst 1978).

Western juniper and its associated ecosystems serve as an essential food source for many migratory birds, mammals, and as shelter or cover for cavity nesters throughout its broad range. Native American peoples traditionally used western juniper wood for making bow staves (Parker 1989).

According to George B. Sudworth, the first Chief Dendrologist in the very early 1900’s with a fledgling organization we now know as the US Forest Service, the western juniper “ is a high mountain tree”. “Because of its uniformly higher range it is not likely to be confounded with the California juniper of a much lower zones [here Sudworth has accepted the common names of the time, with ‘western’ juniper as var. australis, and ‘California’ juniper as var. occidentalis], which it resembles in general appearance”(Sudworth 1908, 1967). Sudworth’s description for the Juniperus occidentalis var. australus rings so true to this author, that it follows intact but for interspersed images supporting Sudworth’s text.

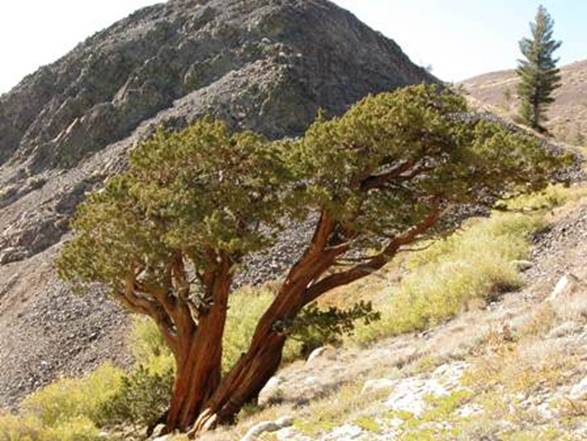

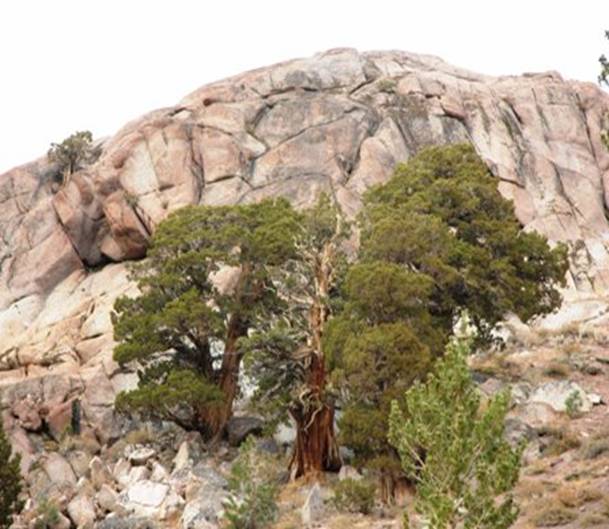

“Western juniper has a round-topped, open crown, extending to within a

few feet of the ground, and a short, thick, conical trunk.

Figure 1

Height, from 15 to 20, or less

commonly 30 feet; only rarely 60 feet or over; taller trees occur in protected

situations; diameter from 16 to 30 inches, exceptionally from 40 to 60

inches. The trunks, chunky and conical

in general form, and with ridges and grooves, are usually straight, even in the

most exposed sites, but are sometimes bent and twisted.

Figure 2

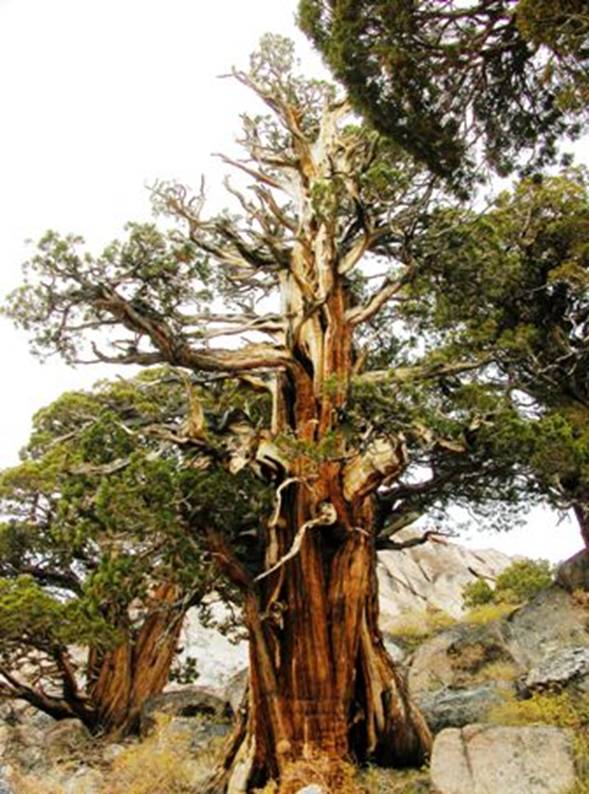

With its stocky form this tree

develops enormously long and large roots which enable to withstand unharmed the

fierce winds common to its habitat.

There is rarely more than from 4 to 8 feet of clear trunk, while huge

lower branches often rise from the base and middle of the trunk like smaller

trunks.

Figure 3

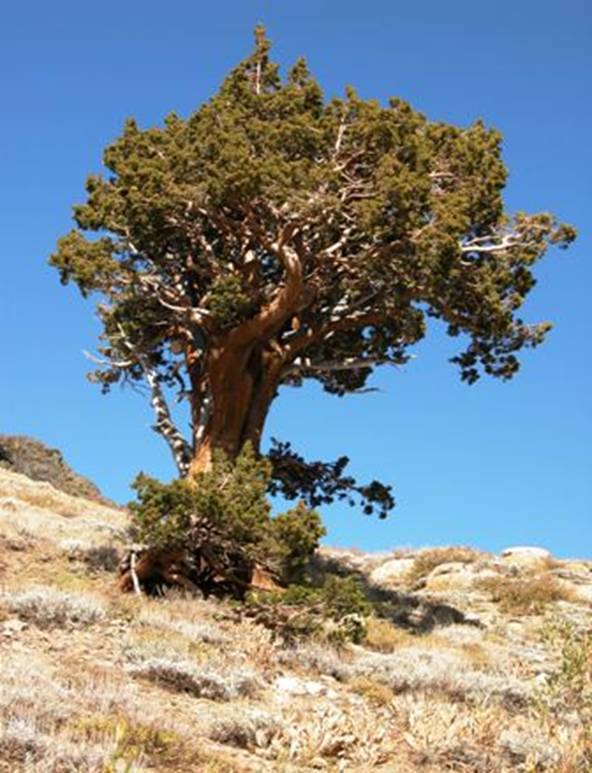

Of the other branches, some are large and stiff, standing out straight

or trending upward from the trunk, while many are short ones. Sometimes the top is divided into two or

three thick forks, giving the tree a broader crown than usual. In such cases, when the trees are growing in

flats with deep soil, the crowns are dense, symmetrical, round-topped, and

conical, and extend down to within 6 feet of the ground.

Figure 4

Young trees have straight, sharply tapering stems and a narrow, open crown

of distant, slender, but stiff-looking, long upturned branches. Often in old age the branches are less

vigorously developed and droop at the bottom and middle of the crown, but their

tips continue to turn upward.

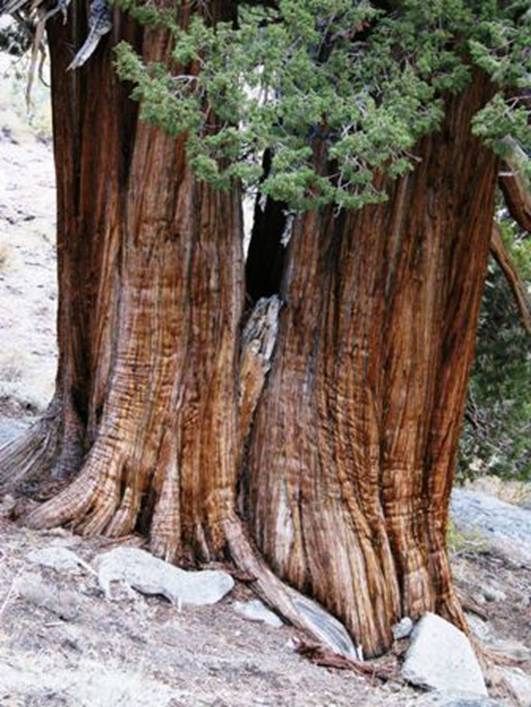

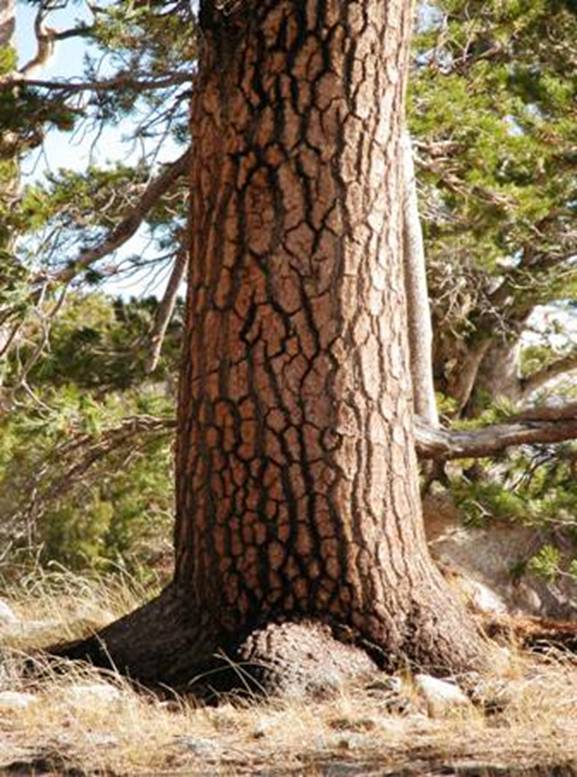

The bark is a clear, light cinnamon-brown, one-half to 1 and 1/4inches

thick, distinctly cut by wide shallow furrows, the long flat ridges being

connected at long intervals by narrower diagonal ridges. It is firm and stringy. Branchlets which

have recently shed their leaves are smooth, and a clear, reddish brown. The bark on them is then very thin, but later

on it is divided into loosely attached, thin scales of lighter red-brown.

Figure 5

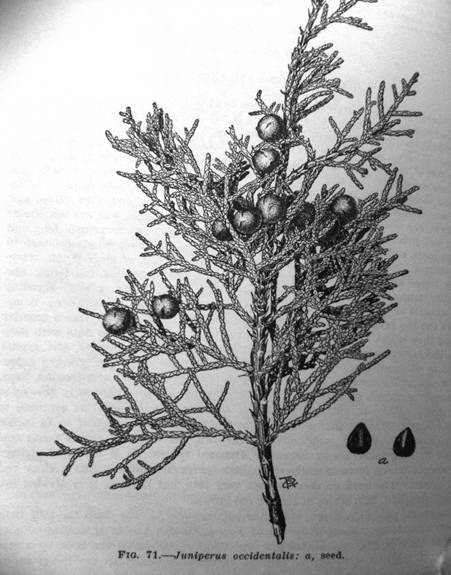

The short, pale ashy-green, scale-like leaves clasp the stiff twigs

closely, the longer, sharper leaves of young, thrifty shoots spreading slightly

only at their points. All leaves are

prominently marked on the back by a glandular pit, whitish with resin. Groups of three leaves clasp the twigs

successively, forming a rounded stem with 5 longitudinal rows of leaves….the berries,

one-fourth to one-third of an inch long, mature about the first of September of

the second year, when they are bluish-black, covered with a whitish bloom;

their skin is tough, and only slightly marked at the top by the tips of the

female flower scales. The flesh is

scanty, dry, and contains from 2 to 3 bony, pitted and grooved seeds, about

which are large resin-cells”. (Figure 71 below is a digital image of a

figure from George B. Sudworth’s “Forest Trees of the Pacific Slope” in the

Dover edition published in 1967, originally a government manual printed in 1908,

and is typical of the detailed pen and ink line drawings found in this text).

Figure 6

All of the digital photographic images in this trip report? (excluding Fig. 71, which was a digital image taken from the cited text), were taken by the author in October of 2008 while traversing the central Sierra Nevada range. Out of curiosity, I had consulted Sudworth’s extensive and intensive ranging by species, perhaps the most detailed listing of all western regional tree guides known by this author to date. Using the Sudworth range descriptions, I travelled from Highway 395 back and forth across the Sierras at Sonora Pass, Ebbets Pass and Kit Carson Pass on a network of California state highways that varied from 9,000 to 10,000 feet in elevation. These passes were also linked by the Sierra Crest or John Muir Trails. Another excerpt from Sudworth follows:

“On east slope of Sierras, common above Jeffrey pine at high elevations; noted in West Walker Canyon (Mono County)

between Antelope Valley and thence southward to Mono Lake, hills about Long

Valley, Sonora Pass and down on ridges and summits in Sierra National Forest at

6,000 to over 10,000 feet elevation.” (Sudworth 1967)

I have personal familiarity with the West Walker Canyon, Antelope Valley, Mono Lake, and Long Valley and can attest to the recent presence of western juniper, almost 100 years after Sudworth’s notes were published. The photos contained in this trip report document the presence of western juniper (var. australis) at Sonora Pass and on into Sierra National Forest. I highly recommend Sudworth for range notes on rare species…he was there, and he tells you where!

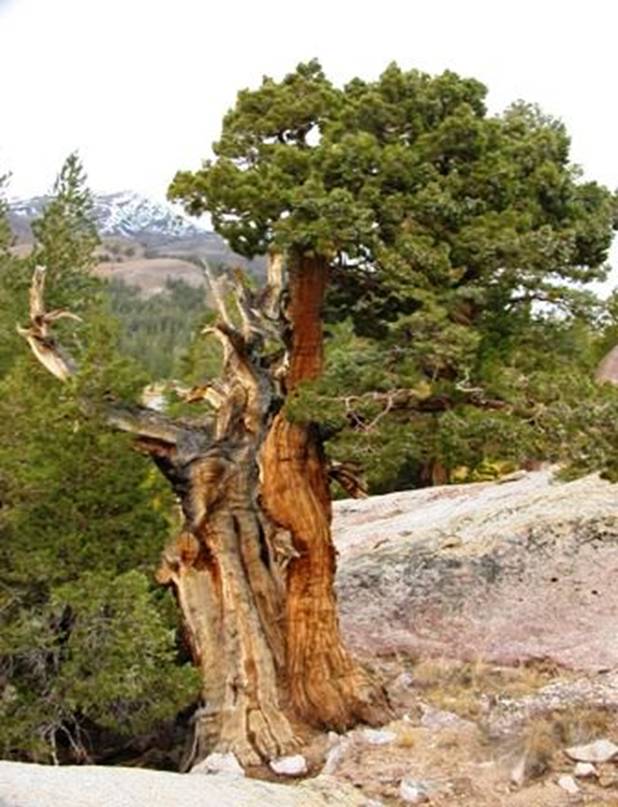

Conditions at these passes were harsh, with high winds, heavy snow loads, strong ultra-violet radiation, and highly variable seasonal precipitation. Some of the images show classic “krumholtzing”, or shaping of foliage by weather (wind, freezing rain or snow driven by winds). Often western junipers will be sustained by unimaginably small amounts of soil and moisture accumulated in interstitial bedrock crevices.

Figure 7

The ability of the western juniper to survive puts then in a small class of other western US conifer species attaining great age despite significant environmental adversity, such as western white pine (Pinus monticola), sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana), ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa), Jeffrey pine (Pinus jeffreyi), whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis), limber pine (Pinus flexilis), foxtail pine (Pinus balfouriana), and most definitively, Great Basin bristlecone pine (Pinus longaeva). Maximum ages for the australis are not unheard of in the 1000 to 1200 year range. The Bennett juniper, which grows near Sonora Pass, California, is believed to be 3,000 to 6,000 years old (Arno 1977; Bronough 1993). It is this author’s suspicion that this is an estimate, with no verified ring count. Both authors have national presence, and Arno has known expertise in this region. That said, there are many western junipers that “look the part”, and I personally wouldn’t be surprised if they occasionally exceeded 3,000 years in age.

An understanding of the fire ecology of the western juniper partly helps to explain its apparent longevity?. With western juniper ‘fire rotation’ averages ranging from 25 to 100 years regionally across the west (average time before wildfire returns to any specific point), it would seem that the western juniper would seldom attain great age. On younger trees the bark is relatively thin, providing little or no protection from even moderate ground fire burn intensities. Western junipers are also characterized by relatively volatile extractives, which serve to accelerate the ignition and burning of foliage.

What permits western junipers to attain greater ages than their average fire return interval? As the western juniper gets older, it puts on thicker bark, and in a self-perpetuating way gets more fire resistant with age. Many of the higher elevation western junipers grow with very low density, across wide granitic expanses with little foliage in between to carry a wildfire. Numerous older western junipers will display signs of lightning strikes, where often large areas of the trunk will be devoid of a cambial layer, relying on strips of remaining live cambium to sustain processes of transpiration and nutrient transfer.

Figure 8

GALLERY

Additional images from the October 2008 Sonora Pass trip follow, with brief comments:

Figure 9

The image above is further up the trunk that the image on the previous page depicts.

The image that follows, displays the broader context – the entire tree and the immediate, and more distant surroundings.

Figure 10

Figure 11

A quite representative western juniper scene here, where a ‘fire safe’ location yields long-lived opportunities for attaining maximum age, despite the exposure to quite harsh elements.

Figure 12

Several western junipers of different age classes and conditions are shown above.

Figure 13

Western Junipers will grow where their seed fell, given the opportunity and the genetics to overcome the harsh environment!

Figure 14

This mountain hemlock was found immediately east of Sonora Pass, with its classic droopy leader.

Figure 15

Much less inclined to height in this setting than its eastern counterpart, this western white pine’s height is likely limited by severe weather crossing Sonora Pass, several hundred feet to the west (right).

Figure 16

The bark characteristics here are common to older western white pines.

Figure 17

Above, typical five needles per fascicle are found on western white pines.

Figure 18

Here we have atypical root growth of an older lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta), perhaps the result of extensive use of some parts of the Sierras for sheep grazing, and the subsequent erosion. Bark characteristics are those of an older lodgepole pine.

Figure 19

Another lodgepole pine with typical old tree bark characteristics

Figure 20

Okay, it’s the reader’s turn to identify this ‘True Fir”. Found a mile back down the road from Ebbets Pass, at about 9,000 feet…points also given to reader that identifies the image with white bark pine in it (Pinus albicaulis)

Figure 21

Yes, our yellow lab Lacey was along, casting a discerning eye over this broader view of the countryside to be found at Sonora Pass…stay tuned for more of Don and Lacey’s Excellent Adventures!

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arno,

Stephen F.; Hammerly, Ramona P. 1977. Northwest trees. Seattle, WA: The

Mountaineers. p.222

Bronaugh, Whit. 1993. The biggest western juniper. American Forests. 99(9-10): 41.

Bunting,

Stephen C. 1990. Prescribed fire effects in

sagebrush-grasslands and pinyon-juniper woodlands.

In: Alexander, M. E.; Bisgrove, G. F., technical coordinator. The art and

science of fire management: Proceedings of the 1st Interior West Fire Council

annual meeting and workshop; 1988 October 24-27; Kananaskis Village, AB.

Information Rep. NOR-X-309. Edmonton, AB: Forestry Canada, Northwest Region,

Northern Forestry Centre: p.176-181.

Budy,

Jerry D. 1984. Biomass and harvesting systems for western juniper. In: Proceedings--western juniper management

short course. 1984 October 15-16; Bend, OR. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State

University, Extension Service and Department of Rangeland Resources: p.53-54.

Dealy,

J. Edward. 1990. Juniperus occidentalis Hook. western juniper. In: Burns,

Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H., technical

coordinators. Silvics of North America. Volume 1. Conifers. Agric. Handb. 654.

Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: p.109-115.

Herbst,

John R. 1978. Physical properties and commercial uses of western juniper. In: Matin, Robert E.; Dealy, J. Edward;

Caraher, David L., eds. Proceedings of the western juniper ecology and

management workshop; 1977 January; Bend, OR. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-74. Portland,

OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Forest

and Range Experiment Station: p.169-177.

Parker, Douglas; Ziegler, Maurice. 1984. Values of western juniper products and a method estimating juniper cordwood. In: Proceedings--western juniper management short course; 1984 October 15-16; Bend, OR. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University, Extension Service and Department of Rangeland Resources: p.55-60.

Sudworth, George B. 1967. Forest trees of the Pacific Slope. Dover Publications, New York: pp181-186.

All images taken by author. For distribution purposes, image sizes have been reduced. For higher resolution versions (generally about 1 megabyte per image), please contact author at

FoRestoration@msn.com