|

==============================================================================

TOPIC: McKittrick Canyon, Texas

http://groups.google.com/group/entstrees/browse_thread/thread/653f7255ae0188ca?hl=en

==============================================================================

== 1 of 1 ==

Date: Sat, Mar 29 2008 7:36 pm

From: "Edward Frank"

ENTS,

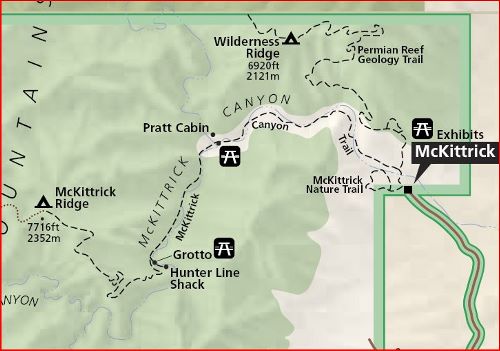

I want to take a trip on the Wayback Machine and revisit a place I

have not bee to for years - McKittrick Canyon, in Guadalupe National

Park, Texas. The park is located just south of the New Mexico border

in western Texas between El Paso and Carlsbad.

McKittrick Canyon is cut into the Guadeloupe Mountains and contains

a relict population of ice age flora growing along an intermittent

stream. The trees include among others Big Tooth maple, Texas

Madrone, Little Leaf Walnut, Honey Mesquite,, and Mexican Buckeye.

At higher elevations are Juniper, Pinyon Pine, Douglas Fir, and

Ponderosa Pine.

Texas Madrone (NPS Photo) - Cookie Ballou. The Texas madrone - a

rainforest relict tree - grows to about 30 feet. It has a gnarled

trunk with reddish bark that peels with age.

Texas Madrone (NPS Photo) - Cookie Ballou. The Texas madrone - a

rainforest relict tree - grows to about 30 feet. It has a gnarled

trunk with reddish bark that peels with age.

Bigtooth Maple in Fall (NPS Photo) - Cookie Ballou. Though much of

the park is beautiful desert terrain, most park visitors prefer to

hike trails that take them into the trees.

Bigtooth Maple in Fall (NPS Photo) - Cookie Ballou. Though much of

the park is beautiful desert terrain, most park visitors prefer to

hike trails that take them into the trees.

This is is sharp contrast to the Chihuahuan desert flora more common

in the area. These include Prickly Pear cactus, Agave, Creosote

Bush, Ocotillo, Choya, and a wide variety of other desert scrub and

cacti.

NPS Photo - Cookie Ballou

NPS Photo - Cookie Ballou

The NPS website describes the canyon: "While

the towering walls of McKittrick Canyon protect the riches of

diversity, its precious secrets are hidden in riparian oasis. It is

no wonder that it has been described as the "most beautiful

spot in Texas." But for all its magical power that delights

thousands of people each year, its fragility reminds us that our

enjoyment cannot compromise its necessity for survival. It must

survive - not for us, but for all that lives within. Thousands of

visitors come to Guadalupe Mountains National Park to visit

McKittrick Canyon each year, especially during the latter part of

October or early November for the sensational fall colors. In this

tiny part of west Texas, the foliage (brilliant reds, subtle

yellows, and deep browns) contrasts dramatically with the flavor of

the arid Chihuahuan desert that includes century plants, prickly

pear cacti, blacktail rattlers, steep canyon walls and crystal clear

blue skies. Whether you come for the fall show, or plan your trip

for another season, the beauty of McKittrick Canyon is always

breathtaking."

Having grown up in the Eastern United States, and seeing the fall

colors here, I am afraid I must agree , the fall colors of

McKittrick Canyon are among the most spectacular I have seen

anywhere. There is the bright colors of the maples standing in sharp

contrast to the stark surroundings. There are the strange

juxtapositions of epiphytic prickly pear cactus and mistletoe

growing among the tree branches. The Texas Madrone, a strange tree

to 30 feet high, with reddish bark that peels off to reveal a white

under-bark adds a further taste of exotic to the scene. I have many

photos of the area, but unfortunately these are in slide format, and

I have yet to scan them. I do have a couple shots I scanned from

older (faded) prints below. I visited Guadalupe National Park and

McKittrick Canyon many times during the period I worked at Carlsbad,

NM.

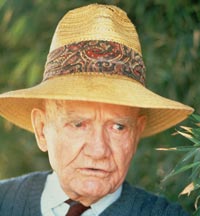

Origin of the Park

The NPS website gives a brief history of Guadalupe National Park: "In

1921, a young geologist named Wallace E. Pratt came to McKittrick

Canyon. He was captivated by its beauty and geology and began buying

land in the canyon. In 1931-32, he had a cabin built at the

confluence of north and south McKittrick. The magnificent structure,

built only of stone and wood, was furnished with rough plank

reclining chairs, four beds, an assortment of hammocks, and a

special table to seat twelve. The cabin served as his part-time home

and summer retreat."

NPS Photo - In 1957, Wallace Pratt donated 5,632 acres of his

beloved McKittrick Canyon to the U.S. Government which formed the

core of Guadalupe Mountains National Park.

NPS Photo - In 1957, Wallace Pratt donated 5,632 acres of his

beloved McKittrick Canyon to the U.S. Government which formed the

core of Guadalupe Mountains National Park.

In 1957, Wallace Pratt donated 5,632 acres

of his beloved property to the U.S. Government for the creation of a

national park. His gift along with a 70,000 acre purchase from J.C.

Hunter Jr.'s Guadalupe Mountain Ranch ensured that Guadalupe

Mountains National Park was authorized by congress in 1966, and

officially opened to the public in 1972. Wallace Pratt died on

Christmas Day, 1981; he was 96 years old. As per his request, his

ashes were spread over the canyon he loved. The Stone Cabin remains

as a monument to this pioneer conservationist."

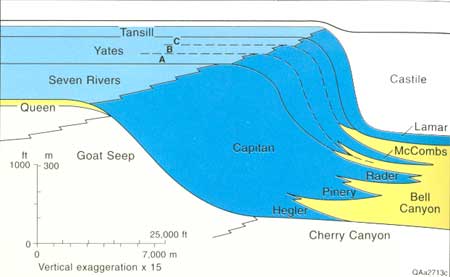

Geology

In Guadalupe National Park, Carlsbad Caverns National park

immediately to the north, and the Guadalupe Mountains in beyond

Carlsbad Caverns in an exposure of one of the most extensive fossil

reef complexes in the world. The core of the reef is made of the

Capitan Reef Formation, a limestone deposit dating from the Permian

Period around 250 million years ago. This reef formed around a vast

tropical sea covering much of west Texas and southeastern New

Mexico.

http://www.nps.gov/gumo/naturescience/upload/reefmap.pdf

In terms of scale think of it as being similar nature to the Great

Barrier Reef off Australia's eastern coast today. When people think

of reefs, they see hoards of fish swimming among corals. That is

true, but the vast bulk of the calcite deposited in reefs are

deposited by the much less spectacular calcareous sponges, algae,

and other lime secreting organisms. The Permian reef ran parallel to

the coast for 400 miles. The Texas version of El Capitan, Guadalupe

Peak, the tallest mountain in Texas, and Carlsbad Cavern in New

Mexico are all exposures or developed within the core reek itself.

The "complex" represents the reef itself and deposits

behind the reef and in the central basin itself. This area in the

center is called the Permian Basin and is the foremost oil producing

section of western Texas.

Cross section showing shelf-to-basin correlations of the Capitan

Formation and equivalents. Blue areas are dominantly carbonates and

evaporites, and yellow areas are mostly sandstone. Modified from

Garber and others (1989). http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/gumo/1993_26/intro.htm

The above diagram is a simplified cross-section of the major

geologic formations in the reef complex. The actual interfaces

between the various units are more complex, but this is a fair

generalization of the geology of the area. More detailed

descriptions of the reef complex can be found at the link above and

at this site: http://geoinfo.nmt.edu/staff/scholle/guadalupe.html

- An Introduction and Virtual Geologic Field Trip to the Permian

Reef Complex, Guadalupe and Delaware Mountains, New Mexico-West

Texas by Peter Scholle.

The NPS Website http://www.nps.gov/gumo/naturescience/geologicformations.htm

reads: "During the late Permian

Period, a reef developed near the border of the Delaware Sea. This

was the Capitan Reef, recognized as one of the premier fossil reefs

of the world and best exposed in the Guadalupe Mountains. Growth of

this massive reef ended near the close of the Permian Period. For

several million years, the reef had expanded and thrived along the

rim of the Delaware Basin, until events altered the environment

critical to its growth. The outlet to the ocean was restricted and

the Delaware Sea began to evaporate faster that it could be

replenished. Minerals began to precipitate out of the vanishing

waters and drift to the seafloor forming thin bands of sediments.

Gradually, over thousands of years these thin bands entirely filled

the basin and covered the reef." This massive

evaporation led to the deposition of the Castille Formation. This

deposit is an amazing 1500 to 2000 foot thick mixture of interbedded

gypsum and salt deposited in a period of about 100,000 years. I

found a photo of a sample from the unit at: http://clasticdetritus.com/2007/12/15/a-few-of-my-favorite-pet-rocks/

Each of the layers in the rock represents the deposition of one year

of sediment. The darker layers are those that incorporate some

terrestrial sediment washed in during the wet season into the

semi-enclosed basin. For the most part the unit was deposited as

gypsum with some salt layers as well. There is no real parallel to

this process gong on today, but the closest would be some of the

fingers off the Red Sea. As sea water evaporates the components

dissolve in the water precipitate out in a certain order. First

precipitated is calcite CaCO3, This precipitated near the inlet of

the basin and served to further restrict water low inward. The next

component that drops out is gypsum CaSO4 · 2H2O. With further

evaporation the next to precipitate is salt NaCl. Finally with

complete or near complete evaporation the most soluble components,

KSO4, MgSO4, KCl, and MgCl, collectively known as potash

precipitate. There are deposits of these minerals in eastern New

Mexico that have been deep mined. One of these sites was used to

house the WIPP, the Waste Isolation Pilot Project to house low level

nuclear waste - items such as gloves used by people handling

radioactive materials and the like. In the short period of time of

Castille deposition the basin deepened as more material was

deposited. This sagging under the weight of the mineral deposits

allowed the accumulation of such a thick deposit in what was a very

shallow sea basin. The Castille Formation is interesting. Hundreds

of cores have been drilled through the rock in search for oil. Near

the base the layers are often contorted and twisted looking much

like a marble cake. This is a result low grade, low temperature, and

low pressure metamorphism of the gypsum CaSO4 · 2H2O to anhydrite

CaSO4 . In this process the mineral recrystalizes into a different

crystal form expelling the water from the mineral structure. The

downside is that the volume of the anhydrite plus the expelled water

is larger than the gypsum was originally. Therefore the pressure

created by increased volume causes the layers to swirl to relieve

the pressure. Uplifts and tilting of this region It is a really

great place geologically.

Prehistory

The NPS website reads: "According to

archeological evidence unearthed in and near the canyon, the

earliest inhabitants occupied the area over 12,000 years ago. Only

stone-chipped tools, bone fragments and bits of charcoal remain to

reconstruct the ways of their lives. More recent discoveries, such

as mescal pits and pictographs, help weave a more complete story of

prehistoric life in the Guadalupes. Much later in history, around

the early 1500s, the Mescalero Apaches inhabited the canyon. The

Guadalupes provided ample supplies of game, water, and shelter

locations, and remained their unchallenged sanctuary until the

arrival of settlers, cattle drovers, and stage lines. As the land

was taken from the Indians, conflicts arose. Skirmishes turned to

bloody battles. Settlers demanded protection. The Mescalero were

forced from the area as cavalry troops penetrated the Guadalupes,

raiding and destroying Apache rancherias, rations and supplies. By

the late 1800s, nearly all of the surviving Mescalero Apaches in the

U.S. were on reservations. Eventually the rugged land was tamed for

ranching and farming. Grazing and hunting activities took their toll

as fences went up. Wildlife disappeared - Merriam's elk, desert

bighorn sheep, and blacktail prairie dogs were all extirpated from

the Guadalupes as a result of extensive hunting and trapping. Though

settlement occurred slowly in the Guadalupes, people were here to

stay. McKittrick Canyon was named for one of those settlers -

Captain Felix McKittrick, a rancher who moved to the mouth of that

canyon in 1869."

McKittrick Canyon Trailhead

There are a number of places you can visit at Guadalupe Mountains

National Park, I will concentrate on the McKittrick Canyon area.

The signature peak of the Guadalupe Mountains, 8,085-foot El

Capitan. (NPS photo by Cookie Ballou)

At the McKittrick Canyon trailhead there are three trails to choose

from. The first is the McKittrick Canyon Nature Trail. This is a

no-brainer to visit. It is a short trail that everyone should

explore before moving onto longer trails. The NPS website reads:

"McKittrick Canyon Nature Trail - An intermittent seep lies

hidden within junipers, shrubs, and grasses that cling to this tiny

ecosystem. Trailside exhibits describe common plants, reference

wildland fire, and explain Permian Reef geology. The trail is .9

miles round trip, is rated moderate, but takes less than one hour to

complete."

The next choice is between the McKittrick Canyon Trail and the

Permian Geology Trail. The Permian Geology Trail leads eastward and

upward toward Wilderness Ridge. The trail includes a series of

interpretive displays and sign explaining the geology of the park as

well as spectacular views from atop the ridge. The trail is 8.4

miles round-trip, and is rated strenuous with 2,000 feet of

elevation gain.. The McKittrick Canyon Trail follows along the

course of an intermittent stream along the bottom of McKittrick

Canyon before rising to McKittrick Ridge and points farther west.

The mouth of the canyon starts out in the Chihuahuan Desert. The NPS

website reads: "The mouth of

McKittrick Canyon is predominately scrub desert where yuccas like

the "Spanish bayonet" (Yucca faxoniana), sotol (Dasylirion

leiophyllum), and ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens) thrive. To the

untrained eye, it seems impossible for anything to grow in such

harsh conditions, yet the plants have evolved to meet the

challenge."

Torrey Yucca

Torrey Yucca

Ocotillo-

the plant only has leaves when there is wet weather. Individually

they resemble barberry leaves. During dry periods the ocotillo oses

its leaves and flowers and resembles a bouquet of dried sticks

standing upright in the desert. Ocotillo-

the plant only has leaves when there is wet weather. Individually

they resemble barberry leaves. During dry periods the ocotillo oses

its leaves and flowers and resembles a bouquet of dried sticks

standing upright in the desert.

Several species of prickly pear cacti (Opuntia

sp.) live in the canyon as well. Their beautiful yellow-orange

blossoms can be observed across the landscape in late spring, and if

your timing is right, you may also enjoy the brilliant red-orange

blossoms of the claret cup cacti (Echinocereus triglochidiatus).

Cactus

bloom - photo by Edward Frank Cactus

bloom - photo by Edward Frank

Cacti and other desert succulents avoid

drying out by storing water in their succulent tissues. To protect

from water evaporation, the stems have a thick waxy coating. Their

leaves, reduced to needles, provide protection from predators while

reflecting the radiant heat of the sun."

From this entrance area the trail takes you under the trees of the

main canyon itself. The NPS website: http://www.nps.gov/gumo/naturescience/trees.htm

and http://www.nps.gov/gumo/naturescience/shrubs.htm

provides a description of some of the more prominent trees and

shrubs that you will encounter on the trip. It is also worthwhile to

pick up a guidebook for the area before arriving that identifies a

broader range of plant species and you can also carry it with you as

you explore.

Pratt

Cabin NPS Photo - Cookie Ballou. During summers when Houston, Texas

is hot and humid, the Pratts and their three children spent time in

the Guadalupes, sharing the cabin with friends. Pratt

Cabin NPS Photo - Cookie Ballou. During summers when Houston, Texas

is hot and humid, the Pratts and their three children spent time in

the Guadalupes, sharing the cabin with friends.

Enjoy the shortest distance into the heart

of the canyon by hiking to Pratt Cabin and return (a distance of 4.8

miles). Along this walk you will cross the stream twice before

arriving at the historic structure. Enjoy a snack or lunch at the

picnic tables near or at Pratt Cabin, or sit for a spell on the

porch. Volunteers staff Pratt Cabin much of the year; take a look

inside the stone structure.

Two McKittrick Canyon Views - photos by Edward Frank

The Grotto

As you continue your hike beyond Pratt Cabin to the Grotto, the

forest becomes denser as the trail runs parallel to the stream.

Rainbow trout are visible in the clear water. At the junction ahead

(approximately 1 mile), take the left fork to go to the Grotto.

There, the dripping water percolates through the limestone,

methodically redistributing calcium carbonate into stalagmites and

stalagmites in the tiny "cave." Rock benches and tables

await you in the deep shade, a tempting location for a picnic.

Follow the stone path from the Grotto to Hunter Cabin, a structure

which was once part of a hunting retreat. Look up the canyon slope

and see the steep switchbacks where the trail continues to

McKittrick Ridge. Round-trip distance from the contact station to

the Grotto is 6.8 miles.

McKittrick Ridge

If you have the endurance and the time, take the right fork at the

Grotto trail junction and continue toward McKittrick Ridge. This

arduous hike takes you up the steepest trail in the park. In a mile

or so the trail passes through "The Notch", where there is

a spectacular view of the canyon both directions. As you continue,

don't be fooled by the false summits that make you think you've

nearly reached the top! The hike from the contact station to the

ridge and back is 14.8 miles. (7.4 miles one way to McKittrick Ridge

Campground).

Creosote Bush - (NPS photo) Larrea tridentata is one of the most

long-lived and abundant desert plants of North and South America. It

is often found in pure stands. The small, leathery, evergreen leaves

occur in pairs united at the base. When it rains, five-petaled

flowers appear and the air is permeated with the fragrance of

creosote bush. The fuzzy white seed balls are relished by rodents.

When crushed, the resinous leaves smell like the petroleum.

Creosote Bush - (NPS photo) Larrea tridentata is one of the most

long-lived and abundant desert plants of North and South America. It

is often found in pure stands. The small, leathery, evergreen leaves

occur in pairs united at the base. When it rains, five-petaled

flowers appear and the air is permeated with the fragrance of

creosote bush. The fuzzy white seed balls are relished by rodents.

When crushed, the resinous leaves smell like the petroleum.

You are likely to encounter a number of wildlife species on your

travels. There are plenty of small lizards - skink, horned lizards,

collard lizard. There are a variety of snakes including western

diamondback.

There are a variety of birds and mammals also. Mammal, bird, and

reptile checklists are available from the Natural History

Association bookstore located at the Headquarters Visitor Center.

There are over 50 species of mammals alone, and more than 300 bird

species that live in, or migrate through the park. 40 of those have

been known to nest in McKittrick Canyon.

I had an unusual encounter with collard lizard while photographing

at Carlsbad Caverns. I was exploring a short trail just off the cave

entrance. There was a collard lizard posing in the sun, so I

squatted down to take a photo. I had a short 200mm telephoto lens on

my camera and was snapping away, when the lizard started to

approach. Soon it was within the minimum focal length of my lens. So

I just sat there and watched. Eventually it approached within 3

feet. The next thing knew the lizard had launched itself at me and

landed on my leg. I jumped and fell over defeated by an 18"

long lizard. Oh well,.at least I lived to fight another day.

Edward Frank

==============================================================================

TOPIC: McKittrick Canyon, Texas

http://groups.google.com/group/entstrees/browse_thread/thread/c1fd0f043eb53f00?hl=en

==============================================================================

== 1 of 2 ==

Date: Wed, Apr 30 2008 10:06 am

From: ForestRuss@aol.com

Ed:

I spent a week in that part of Texas in 1986 when Halleys Comet paid

its

last visit. I went to Big Bend NP because I figured it would be one

of the

darkest places in the country to see it (because you had to go that

far south to

even see it). I hiked to the top of the Chisos Mountains and sat at

the edge

of the 1000 foot cliff and waited, and waited...it wasn't until I

noticed

that what looked like a 15 watt light bulb in a refrigerator rising

straight up

into the sky from the due south that it was going to be a bust. I

ended up

spending several days in Guadalupe NP and I climbed both Guadalupe

Peak and

hiked McKittrick Canyon...the thing that resonated with me the most

was all the

species of trees that are found there as glacial remnants and in

many cases

more than a thousand miles out of their modern range. You wrote an

exceptional report on a unique part of the country. The white pine

trees in the

Guadalupe Mountains were nuked by major forest fires a few years

ago.

Russ

== 2 of 2 ==

Date: Wed, Apr 30 2008 10:21 am

From: "Edward Frank"

Russ,

I enjoyed hikes tat McKittrick Canyon numerous times, but haven't

made it to Big Bend yet. I posted to try to expand the

"range" of areas being discussed in the list. I thought

the glacial remnant populations were an unusual subject to be

broached on the list, but this is actually the first response to the

McKittrick Canyon post. If you hear anymore about the Webster

Sycamore live/dead status let us all know.

Ed

|