ENTS

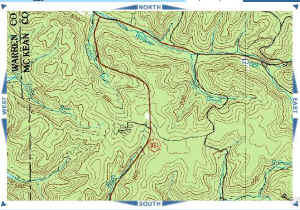

Carl Harting and I visited an area known as Chestnut Ridge just

east of

route 321 a couple miles east of the Allegheny Reservoir,

colloquially

known as Kinzua Dam.

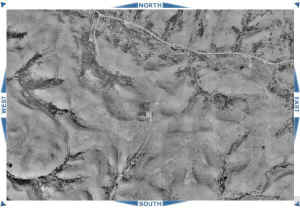

Maps of areas from mapquest |

|

We parked beside the road and headed into

the forest

going east and little southward. We found ourselves in a young

second

growth forest. I estimated 30 years, Carl 50 years. It consisted

of an

overstory dominated by white oak. The understory was heavily

populated by

striped maple, cucumbertree, and American Chestnut. The chestnut

trees were

everywhere. Most were less than 20 feet high with some

individuals going as

tall as 40 feet. The trunks all were small in diameter. Soon we

found an

old overgrown road and decided to follow it across the ridge.

The road ran

eastward and slowly curved slightly to the north. Here and there

were

larger specimens of American Chestnut, Some reaching an

estimated 50 feet.

The tallest we measured was (71.3 feet tall and 2 ˝ feet in

circumference).

It is not what I would have expected, but as you walk upon them

at first

cucumber trees look remarkably like chestnuts until you are

close enough to

discern the differences. Perhaps they have a similar branch

pattern, or

leaf out pattern, but at first glance they look very much alike.

Largest American Chestnut measured. |

|

[Carl notes: I'd like to add chestnut oak

into the mix of trees that the

chestnuts were associated with. They may not have been quite as

numerous

as

the cucumbers and other oaks, but they were definitely there.

While the

cucumber and striped maple are missing in the chestnut habitat

on the ridges

above the Clarion River, the chestnut and other oaks are present

there.

Chestnut oak are also very difficult (at least for me) to

differentiate from

American chestnut at a distance, especially when the bark is not

visible.

The trio of Am Chestnut, chestnut oak and cucumber at this site

was tough to

read quickly. As with the other chestnut sites, the chestnuts

were only

found on the ridges, never in the valleys.]

It had been raining earlier in the day, and I had not been sure

the trip

would go off as planned. I met Carl at Cook Forest and we car

pooled to the

site. I brought my raingear. It turned out that

we avoided most of the

showers and had a pleasant day for the walk. It had rained for

several

days. Mushrooms and fungus were growing everywhere. There were

numerous

frilly orange unidentified species, browns, white, purples and

reds. I saw

at least two varieties of coral fungus.

From there we continued along the road looking for taller

specimens with

little luck. After a short distance we arrived at a dirt and

gravel road

trending north. We followed this road and began a slow descent

from the

ridgetop. As we descended the types of trees changed to one

containing more

red oaks, maples, and a few tuliptrees and bigtooth aspen. We

stopped and

measured a couple of them, but no records were set. I was still

amazed at

the variety of fungi growing in the area. Even

in this out of the way

stretch of road there were still occasional piles of trash down

th hill

slope from the road. One had a number of cans and several

plastic 5 gallon

plastic buckets.

Tuliptree |

Dead tree with fungus growth |

As we approached the bottom of the hill a stream grew nearer to

the road.

In the bottom portion of this journey we started to find some

hemlock,

hornbeams and a few others. At this point we decided the road

was not going

the correct direction as shown on my GPS unit map, so we took

off and headed

cross country westward. Route 321 was a little over a half mile

in that

direction.

[Carl notes: the heights of the small area

of taller trees, and mention

that this forest was older than that found on the ridge top (at

least it

looked a good bit older to me, especially with the red maple

having the

shaggy bark and the large oaks were found as we were climbing

out of the

valley).]

tallest chestnut CBH 2ft 6in height 71.3 feet

tulip CBH 8ft 2in height 125.1ft

white ash CBH 4ft 8in height 114.5ft

bigtooth aspen CBH 4ft 9 in height 96.1ft

Tree with a series of branches growing out of its

side from epicornic sprouts. |

Roadside Plant: Alianthus? |

A short distance into the woods we cam across a stream. It did

not look

very wide or deep, but was flowing pretty rapidly. We decided to

cross anyway.

Going cross-country was not the best idea I ever had. All of the

elevation we l

ost up to that point, was regained in this single climb. I had to stop

several times

and catch my breath, those overhangs are murder. During one of

those pauses

a hawk flew down from a tree very agitated near Carl, but did

not see it

engrossed in the examination of a tree on the hillside. It flew

off.

Once we reached the top, it was a a fairly straightforward shot

back to

route 321. On the flats we again started to encounter striped

maple,

cucumbertree, and chestnut. Here also were some tuliptrees and

beeches,

with overstory white and red oaks. I wondered about the

association between

the striped maple, cucumbertree, and American chestnut. It

seemed to be the

norm here, but was not the same at other chestnut locations we

had visited.

Perhaps it was coincidental. Soon we were back at the road. It

was a short

walk along the highway back to the car. We arrived just as the

rains

started to fall.

Immediately south along the road we turned into the the Tracy

Ridge

Campground for a quick drive through on the same ridge for a

quick look.

The place had hundreds of American Chestnut trees. Most were

small, a

couple we saw from the car might have reached 50 feet. Given the

number we

saw, and the fact that wee found a 71+ footer elsewhere on the

ridge, it

would be worthwhile to revisit the campground area for a

reconnaissance of

chestnuts and other trees present. From here we head back to

Cook Forest

and on to home.

This was our trip more or less. Nothing really exciting or

unusual

happened. We found some interesting forest, but nothing really

old or big.

This had to be the densest population of American Chestnut I had

ever seen.

Some reports suggested in areas that American Chestnut had made

up to 70%

of

the basal area in given stretches of the forest. None of the

trees looked

mature enough to produce nuts and were likely root sprouts. If

the blight

doesn’t get them they may produce nuts in a few years. With

such a high

density of trees there is even a good chance of pollination from

other

individuals and the production of viable nuts. Keep your fingers

crossed.

Ed Frank

Sept 14, 2006

|