|

==============================================================================

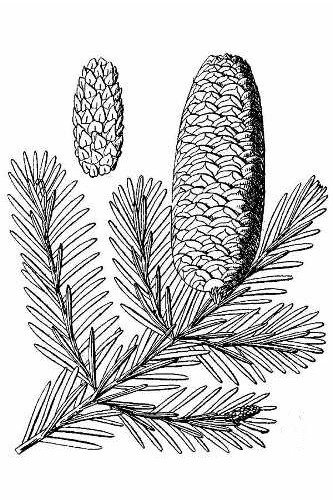

TOPIC: Abies balsamea - a southern disjunct populatiom - sort of

http://groups.google.com/group/entstrees/browse_thread/thread/55d5a418079c1999?hl=en

==============================================================================

== 1 of 2 ==

Date: Sun, Aug 17 2008 9:11 pm

From: "Edward Forrest Frank"

ENTS,

Today I went looking for a disjunct population of balsam fir on the

southern end of its range in central Pennsylvania. I found them -

sort of. The tale started with a note on the website for Black

Moshannon State Park. http://www.dcnr.state.pa.us/stateparks/parks/blackmoshannon.aspx

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Moshannon_State_Park

Background:

Perched Black Moshannon State Park covers 3,394 acres of forests and

wetlands, and includes 1992 acres which are protected as the Black

Moshannon Bog Natural Area. The bog in the park provides a habitat

for diverse wildlife not common in other areas of the state, such as

carnivorous plants, orchids, and species normally found farther

north. This bog is the largest reconstituted bog/wetland complex in

Pennsylvania with the Black Moshannon Lake and the associated bogs

are held behind a dam on Black Moshannon Creek, The CCC-built dam

forming Black Moshannon Lake was replaced in the 1950s by the

current structure. The park is atop the Allegheny Plateau, just west

of the Allegheny Front, an escarpment which steeply rises 1,300 feet

(400 m) in 4 miles (6.4 km), and marks the transition between the

Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians to the east and the Allegheny Plateau

to the west. The lake within the park is at an elevation of about

1,900 feet (580 m), and the park itself sits in a natural basin. The

basin and the underlying sandstone trap water and thus form the lake

and surrounding bogs. The higher elevation leads to a cooler

climate, and the basin helps trap denser, cooler air, leading to

longer winters and milder summers.

Black Moshannon Lake

The Hint:

Star Mill Trail: With fine views of the lake and opportunities to

see wildlife, this trail travels through pines, a climax forest of

beech and hemlock and an UNCOMMON STAND OF BALSAM FIR. Look for

evidence of Star Mill, a sawmill which was built in 1879. (1.1 mile,

2.0 full loop, flat, hiking, cross-country skiing)

If you look on a map of the distribution of balsam fir, there are

several disjunct populations trailing off along the Appalachians

southward from the primary range into West Virginia and Virginia.

I wanted to see what the species looked like near the southern end

of its range. Some people have looked at the populations in West

Virginia and determined they may be a separate subspecies of balsam

fir - a "bracted" variety, A. balsamea (L.) Mill. var.

phanerolepis, more closely related to the typical balsam fir A.

balsamea (L.) Mill. var. balsamea than to Frazier Fir Abies fraseri

(Pursh) Poir. West Virginia Seed Sources of Balsam Fir http://ohioline.osu.edu/rb1191/1191_17.html.

I stopped at the park office and spoke to the park manager Chris

Reese. My question was whether or not these were truly a disjunct

natural population or a planted population that was naturalizing.

The answer was that he was unsure, because different people have

suggested both options. After talking to him I headed to the Star

Mill Trail. The area was essentially timbered flat in the late

1800's and I expected to see second growth forest associated with

regrowth from that period. I found that. The other thing that really

jumped out was the large population of exotic conifers ranging from

red pine plantations planted by the CCC in the 1930's to a variety

of different spruces growing among a hemlock and red maple dominated

second growth forest. I found some trees along the trail that were

pretty good size. I measured a Hemlock with a girth of 9' 4".

|

|

Large Hemlock

This was not then only hemlock of size. It looked old, so did a

number of other specimens of hemlock along the trail. They likely

were spared from logging as they were not prime timber. I also found

some large red oak trees one was 9' in girth and 95 feet tall, the

second was 9' 9" in girth and 103 feet tall. These could very

well post date the lumbering operation. There were a number of

twisted but fat white pines along the trail also.

Red Oak |

White Pine |

I did find the balsam firs. The largest were in the neighborhood

of 5 inches in diameter and perhaps 40 feet tall. The largest and

oldest were in the central portion of the grove. Scattered and

generally progressively younger firs were found up to 150 yards from

the central portion of the balsam fir grove. Now for the kicker. The

largest and oldest firs, and I am not very familiar with the age

characteristics, were associated with a linear series of arborvitae

of similar size. It was my impression these arborvitae had been

planted along a lane. The juxtaposition of the arborvitae and the

oldest and largest of the balsam firs, the fact that they were

comparable in size, and the fact that the arborvitae were planted

lend credence to the idea these balsam fir were also a planted

population.

|

|

I searched the area for older trees and failed to find them. This

group was found along the southern end of the Star Mill Trail in on

a strip of land lying west of Beaver Road and an east of an arm of

Black Moshannon Lake. I did find a single balsam fir on the east

side of the road uphill from the site, but there were no additional

seed sources uphill of this individual. The USDA Silvics Manual

reports: "Seed Production and Dissemination- Regular seed

production probably begins after 20 to 30 years. Cone development

has been reported for trees 15 years of age and younger and only 2 m

(6.6 ft) tall. Good seed crops occur at intervals of 2 to 4 years,

with some seed production usually occurring during intervening

years. These are about 134 seeds per cone. The period of balsam fir

seedfall is long and dissemination distances vary. Seedfall begins

late in August, peaks in September and October, and continues into

November. Some seeds fall throughout the winter and into early

spring. Most of the seeds are spread by wind-some to great distances

over frozen snow-and some are spread by rodents. Although seeds may

disseminate from 100 m (330 ft) to more than 160 m (525 ft),

effective distances are 25 m to 60 m (80 to 200 ft) (1,11,28). Many

seeds falling with the cone scales land close to the base of the

tree." I would suggest that the seeds may also be dispersed by

animals and birds beyond that range. In any case it certainly is

feasible that the entire population was propagated from a single

seed source. If balsam fir were planted in conjunction with the

arborvitae, there may have been multiple sources for the current

population.

The first question to my mind is how do you tell if this is a

regrowth of a native population or one derived from a planted seed

source? I don't know if there is a way to tell indisputably. Looking

at the evidence you have: 1) a fairly young population, 2) a

population that appears centered on a single area, 3) the age

distribution appears to get progressively younger away from the

center, 4) the species has not spread a great distance from the

center, 5) the center of the population is associated with a planted

population of arborvitae, 6) Superficially the arborvitae seems

comparable in age to the oldest of the balsam fir.

Chris Reese told me that there was a single older balsam fir of

unknown origin near another park building. I have yet to check this

specimen out. Aside from this, there does not appear to be any

additional balsam fir in the park. I would think if this was a

native population that was reestablishing itself after being cut

down, that there would be more than one locality with the species in

the park. There are other, more southerly populations of the

species. Clearly looking at things such as the pollen record, firs

were present in the area during the end of the last glaciation. So

this is within the potential range for a disjunct population. Mr.

Reese told me that the district forester had concluded that this was

a planted population that is naturalizing in the area. I would based

upon the evidence found also conclude that this is most likely a

planted population that is naturalizing on the site. A potential way

to shed more light on the question is to determine the relative ages

of the oldest fir present and the arborvitae. If they both date from

the same time frame this would lend more credence to the idea they

are derived from a planted population. Mr. Reese gave me verbal

permission to core some specimens. I tried to core one specimen, but

the wood was soft and plugged my corer. I decided to pursue this

coring effort another time.

A second question has been bothering me about this population. If

this population is derived from a planted specimen and is vigorously

naturalizing in the area, should it be considered a naturalized

species or a native species? Looking at the past history of the

site, it supported balsam fir in the past, but I am unsure of how

long it has been since the species was present. Since the species is

naturalizing prolifically, it suggests that the species could exist,

or even thrive there at the present time. Was the species lost from

the site from a slow progression of change, or was it persisting as

a remnant population that was lost in a single event? This is a

prospect faced by our island pockets of preserves. If a species is

lost through some set of circumstances, there may be no sources left

to regrow the lost species population. So is this a case of

naturalization or simply one of reintroduction of a species to a

disjunct portion of its range? I know someone will post a set of

technical definitions with everything spelled out, but I am

wondering about the core nature of the concepts of native,

naturalized, and reintroduced rather than the compromises required

of most technical definitions.

Ed Frank

Miscellaneous Links on Balsam Fir:

USDA Silvics Manual

http://www.na.fs.fed.us/pubs/silvics_manual/volume_1/abies/balsamea.htm

USDA Plant profile Abies balsemea

http://plants.usda.gov/java/profile?symbol=ABBA

Balsam Fir pdf

http://www.fpl.fs.fed.us/documnts/usda/amwood/234balsa.pdf

Conifers.org Balsam Fir

http://www.conifers.org/pi/ab/balsamea.htm

Plant profile for Abies balsemea

http://plants.usda.gov/java/profile?symbol=ABBA&mapType=Large&format=Print&photoID=abba_003_ahp.tif

Nearctica - Balsam Fir

http://www.nearctica.com/trees/conifer/abies/Abalsam.htm

West Virginia Seed Sources of Balsam Fir

http://ohioline.osu.edu/rb1191/1191_17.html

http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/abibal/all.html

Pennsylvania County Distribution Map

http://plants.usda.gov/java/county?state_name=Pennsylvania&statefips=42&symbol=ABBA

Balsam Fir Thrives in State's Bogs

http://www.sungazette.com/page/content.detail/id/505706.html?nav=5013

Abies balsemea - Wilkepedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balsam_Fir

Conifers.org reports:

Big Tree

Height 30 m, dbh 120 cm, crown spread 14 m; in Fairfield, PA

(American Forests 1996).

Oldest

A tree-ring chronology covering 245 years, presumably based on

living tree material, was collected in 1996 at Lac Liberal, Canada

(470 m elevation, 49° 4'N, 72° 6' W) by C. Krause and H. Morin (NOAA

1999).

== 2 of 6 ==

Date: Mon, Aug 18 2008 5:56 am

From: ERNEST.OSTUNO@noaa.gov

Ed,

Thanks for the very interesting report. All I remember about

"Black

Mo" was the huge old hemlock stumps left over from the logging

era,

lots of porcupines, and lots of beaver-gnawed trees near the lake.

As for Balsam Fir, have you been to Bear Meadows Natural Area? Dale

Luthringer has a nice write up on that place:

http://www.nativetreesociety.org/fieldtrips/penna/bear_meadows.htm

I also have video of Bear Meadows from 1999 that you posted on

youtube

last year. The area has been studied by the PSU Forestry people, but

I'm not sure if Black Moshannon has. I am guessing not, since it was

almost totally cut over. You could ask Marc Abrams at PSU about

that.

Ernie

== 3 of 6 ==

Date: Mon, Aug 18 2008 8:32 am

From: "Jess Riddle"

Ed,

What jumps out at me from your description and photos is that Black

Moshannon SP does not look like typical habitat for balsam fir at

the

southern edge of the range. In New York outside of mountainous

areas,

balsam fir is restricted to swamps and a few areas of thin limestone

soils. Bear Meadows in PA fits that same pattern. The Black

Moshannon stand looks fairly well drained and does not appear to

have

any unusual soil conditions. Hence, the habitat also seems to

indicate the population is not naturally occurring.

Jess

== 4 of 6 ==

Date: Mon, Aug 18 2008 9:35 am

From: "Edward Forrest Frank"

Ernie,

Yes, I know about Dale's report and posted your video. I wanted to

go to Black Moshannon SP because it was someplace different that had

not been reported on before. The two things that stood out in the

blurbs from the park were the unusual stand of balsam fir and an

unusual stand of hawthorns. I did not see the hawthorns but got a

good location. They really aren't that big or old according to Chris

Reese, but form what is pretty much a monoculture stand of the

species in one area of the park. On their species list the only

hawthorn species keyed out is dotted hawthorn Crategus punctata -

the same species we found in the Allegheny River Islands Wilderness.

I will check it out on a future trip.

Ed

== 5 of 6 ==

Date: Mon, Aug 18 2008 9:42 am

From: "Edward Forrest Frank"

Jess,

The general area overall has been a swampy since the last ice age.

The current impoundment behind the reservoir is not more than a few

feet lower than the trail through the stand, and no more than a

stones throw away. The area of the stand specifically appears to be

well drained, and the oldest portion of the stand is upslope perhaps

another ten to twenty feet higher in elevation than the trail.

Without soil borings I can't really say if the soil immediately

below the surface detritus is drained well or not.

Ed

== 6 of 6 ==

Date: Mon, Aug 18 2008 12:53 pm

From: ERNEST.OSTUNO@noaa.gov

Ed,

I remember there being quite a few small underground springs

bubbling

up on the periphery of the reservoir. In fact I have video somewhere

of a few of them.

Also, I remember reading somewhere, maybe the park brochure, that

the

water table was greatly affected by the clearcutting during the

logging era. I don't know enough about forestry or hydrology to know

if this even possible.

Ernie

==============================================================================

TOPIC: Abies balsamea - a southern disjunct populatiom - sort of

http://groups.google.com/group/entstrees/browse_thread/thread/55d5a418079c1999?hl=en

==============================================================================

== 1 of 7 ==

Date: Tues, Aug 19 2008 3:54 am

From: JamesRobertSmith

Excellent report. Thanks for posting that.

Pennsylvania is one eastern state where I've never been hiking.

Looks

like I've been missing quite a lot.

I'll never forget driving through the state one year to get to

Syracuse NY. In PA and in NY I drove stretches of Interstate that

went

for tens of miles with no sign of towns at all. Then (early 90s)

there

was about a 40-mile stretch in NY where you are warned that no there

will be no gas stations. We drove through at night, and we saw not a

single city light. It was great to see such a wide swath of rural

land.

== 2 of 7 ==

Date: Tues, Aug 19 2008 6:01 am

From: dbhguru@comcast.net

James,

Western New York has several counties with very low population

densities. In fact, New York has an amazing amount of open space.

When you consider the human zoos that have developed in the

Northeast (New York, Boston, Philadelphia, etc.), the western NY

countryside is just great. I love New York state, but I avoid the

Big Apple and the other human termite colonies if at all possible.

Bob

== 3 of 7 ==

Date: Tues, Aug 19 2008 7:13 am

From: turner

Ed. Thanks for post on the Balsam Fir. It will energize me to visit

several of our stands in West Virginia which I have been meaning to

do. I have been told that between heavy deer browsing and HWA most

of

them are not doing to well. Locally they are called Blister Pine -

is

that name used in PA? Also thanks for the link to the OSU research

paper. Very informative and I had not seen it before although I was

aware that the Christmas tree growers really liked the Canaan

Valley,

Tucker County, WV seed source.

TS

== 4 of 7 ==

Date: Tues, Aug 19 2008 9:05 am

From: "Edward Forrest Frank"

Turner,

As far as I know HWA does not attack balsam fir nor Frazier fir.

There is a similar organism a Balsam Wooly adelgid that does attack

them. The following is an excerpt from an overview/introduction to

the Third Symposium on the HWA by Fred Hain:

Third Symposium on Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Presentations -Hain

BALSAM WOOLLY ADELGID: ADELGES PICEAE AND

HEMLOCK WOOLLY ADELGID: A. TSUGAE (HOMOPTERA: ADELGIDAE)

It is interesting to compare the initial significance and spread of

hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA) and balsam woolly adelgid (BWA). BWA

was found in natural stands of balsam fir in 1908 and in Fraser fir

of the southern Appalachians in 1955. Severe mortality was

immediately apparent. HWA was found on ornamental eastern hemlock in

1952 or '54 in Richmond, Virginia, and was not considered a serious

pest because it was easily controlled with pesticides. HWA became a

pest of concern in the late 1980s when it had spread to natural

stands. Since then it has caused widespread mortality. Neither

adelgid is considered a pest in its native range. BWA attacks all

fir species, but Fraser fir is one of the most susceptible. Usually,

mature trees in natural stands are attacked, but trees in Christmas

tree plantations are also attacked. The insect can be found on all

parts of the tree, but it primarily infests the trunk. Old-growth

Fraser fir stands are virtually eliminated, but individual trees

still survive. In many cases, vigorous Fraser fir reproduction has

replaced the old growth, begging the question what will happen to

these trees as they approach the age of maximum susceptibility to

BWA. Early research on BWA emphasized biological control. Six

European predators are known to be established. They are Laricobius

erichsonii (Coleoptera: Derodontidae), Pullus impexus (Coleoptera:

Coccinellidae), Aphidecta obliterata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae),

Aphidoletes thompsoni (Diptera: Cedidomyiidae), Cremifania

nigrocellulata (Diptera: Chamaemyiidae), and Leucopis obscura (Diptera:

hamaemyiidae). However, there has been no clear demonstration that

any of the predators have had a significant impact on BWA

populations. Current research on BWA is emphasizing host factors.

BWA presentations at this conference will deal with impacts in the

southern Appalachians, host interactions, chemical composition of

wood and infested bark, metabolite profiling and microarray analysis

of infested and uninfested fir species, and an artificial feeding

system development for both adelgid species. Unlike BWA, HWA will

attack all ages of its host in natural stands and, consequently,

represents a more serious threat to hemlock than BWA does to fir.

Eastern and Carolina hemlock are very susceptible to HWA, while the

western and Asian species are not. The basic challenge that we face

is to understand why the western and Asian hemlocks are not impacted

by HWA the way Eastern and Carolina hemlocks are: is it biological

control, host resistance, a combination of the two, or something

else? Perhaps the information presented at this conference will

begin to answer this question.

Finding the status of the balsam fir populations in West Virginia

and Virginia would be a worthwhile undertaking. If you visit them

please report to everyone on what you find. ENTS doesn't have any

accounts from these stands.

Ed Frank

== 5 of 7 ==

Date: Tues, Aug 19 2008 9:29 am

From: "Edward Forrest Frank"

Turner,

Regarding the name Blister Pine - I don't really know. I am not a

forester and have never been part of the forestry or lumber industry

community, so I don't know if they call it that or not. Locally the

species is not present so local people really do not call it

anything. They are sold as Christmas Trees and landscaping plants,

but I believe they are just called balsam fir. My knowledge is from

guidebooks and academic papers which call it balsam fir. So I don't

really know.

Ed

== 6 of 7 ==

Date: Tues, Aug 19 2008 3:00 pm

From: Lee Frelich

Jess, Ed:

There are also balsam fir stands in Iowa and southeast Minnesota, in

what

is otherwise a prairie climate. These fir stands are on algific

talus

slopes with cold air ventilation throughout the summer. Behind the

talus

slopes there are caves that fill with ice from groundwater seepage

during

the winter, and it takes all summer for the ice to melt, allowing

cold air

to seep out between the rocks during summer. These stands also have

boreal

understory plants.

Most southern outliers of conifers at this time are actually not

relics

from the last glaciation, but rather advanced populations form

southward

migration which was in progress from about 7000 years before present

until

the early 1900s. They were responding to the natural cooling trend

after

the Mid-Holocene warm period. In some pollen records the conifers

disappear

and then reappear in the last few thousand years. Now with global

warming

tree species are moving rapidly in the other direction.

Lee

== 7 of 7 ==

Date: Tues, Aug 19 2008 3:26 pm

From: "Edward Forrest Frank"

Lee,

If they are part of an advancing front, how did they make the jump

from the present boundaries of their common range to their present

positions tens to hundreds of miles from the next known population

to the north? In the case of Black Moshannon, I think the trees are

naturalizing from a planted specimen, but there is another

population in southern Centre County (I have not visited it yet) far

from the populations in northern PA. There are also pockets in West

Virginia and Virginia. These seem to have some significant genetic

differentiation from the general population of balsam fir. This

would suggest to my mind that they are an older population that has

been isolated for some period of time, rather than the front line of

an advancement. I am not familiar with the specifics of the pollen

record, but say 12,000 years ago there was a mass of Abies sp. in PA

through the southern Appalachians. Now there is Frazier Fir [Abies

fraseri (Pursh) Poir] in the south, these isolated pockets of balsam

fir in West Virginia and Virginia [A. balsamea (L.) Mill. var.

phanerolepis] also known as Canaan Fir - a favorite among many

Christmas Tree growers, these small patches in PA, and the a

generally wide ranging mass that extends from northern PA into

Ontario and westward to Manitoba (maybe Alberta?). How would the

advancing scenario work to explain this distribution of fir pockets?

Do you have some maps or diagrams you could post and references

providing more details?

Thanks for the information about the fir stands in southern

Minnesota and Iowa. This is the kind of unusual mechanisms I want to

ENTS document. Are these populations genetically consistent with

those of the general population in northern Minnesota and Wisconsin?

I would love to be able to document many of the unusual assemblages

of trees and plants you are commenting on from Minnesota both at the

fringe of the glaciations, and on the edge of the forest prairie

transition. It would be great if you could do some short

descriptions of these locations with photos for the ENTS list. maybe

you could recruit some additional ENTS members from out your way,

perhaps among your cult followers there in Grad school.

As always I appreciate these gleanings from your forest repertoire.

Ed

==============================================================================

TOPIC: Abies balsamea - a southern disjunct populatiom - sort of

http://groups.google.com/group/entstrees/browse_thread/thread/55d5a418079c1999?hl=en

==============================================================================

== 1 of 1 ==

Date: Tues, Aug 19 2008 7:02 pm

From: turner

Ed: Thanks for straitening me out about HWA vrs. BWA concerning

Balsam

Fir. When I get a chance to visit a stand I will write up what I

find. The ones I know about are easily accessible but about 3 hours

from home.

TS

==============================================================================

TOPIC: Abies balsamea - a southern disjunct populatiom - sort of

http://groups.google.com/group/entstrees/browse_thread/thread/55d5a418079c1999?hl=en

==============================================================================

== 1 of 2 ==

Date: Wed, Aug 20 2008 6:17 pm

From: Lee Frelich

Ed:

On a long time scale fir clearly was abundant across the east,

including PA

12,000 years ago, and then disappeared (having moved to northern

Quebec)

and came back in the last few thousand years. In MN the pattern is

similar

except that fir was not as abundant 12,000 ybp, and did not a

readvance,

probably because of droughts and fires, until the last 1000 years.

Its

always possible that some populations persisted through the mid

Holocene,

but given the rate of southward movement in the last few thousand

years, it

seems likely that most naturally established spruce and fir sites

along the

southern margin of the species ranges were established in the last

1000-2000 years. Not all of these sites have a sedimentary record,

so there

is still a lot we don't know.

There is only one genetics paper on the topic by Shea and Furnier

which

compared isolated populations in IA and MN to populations in the

central

part of the range, which showed that the isolated populations have

lower

diversity, which could be consistent with a recent founder effect or

loss

of genes through long term isolation.

We know almost nothing about long distance dispersal by plants

during

migration.

Lee

== 2 of 2 ==

Date: Wed, Aug 20 2008 6:33 pm

From: "Edward Forrest Frank"

Lee,

Thanks. I am thinking that perhaps the populations in WV and VA may

be remnants simply because of the differentiation from the genetics

of the population farther to the north.

The situation you describe for the populations in MN with the lower

diversity is analogous to what was found in the Caribbean. http://www.caves.org/pub/journal/PDF/V60/V60N2

-Frank-Paleontology.pdf

One of the consideration of diversity in Caribbean Islands was if

they were slowly populated over time by animal species rafted to the

island they would have a low initial diversity that increased over

time. If they were part of an isthmus connected to the mainland that

became separated into islands by raising relative sea level, then

the initial species diversity would be high - equivalent to that of

the mainland - and this diversity would generally decrease over time

as species were lost.

In this case an advancing population would be established based upon

the genetic make-up of the first or first few examples that reached

the area. Thus a low diversity. If it were a remnant population from

retreat the main body of the population then it would have a higher

initial diversity in the population, and frankly it is hard to get

rid of diversity without it being replaced by a genetic change that

is better suited for the environment.

Ed

==============================================================================

TOPIC: Abies balsamea - a southern disjunct populatiom - sort of

http://groups.google.com/group/entstrees/browse_thread/thread/55d5a418079c1999?hl=en

==============================================================================

== 1 of 2 ==

Date: Thurs, Aug 21 2008 3:05 pm

From: Lee Frelich

Ed:

You might be right, the firs could have survived the mid-Holocene at

high

elevation. However, I don't think we'll know for sure unless more

detailed

studies are done.

Lee

== 2 of 2 ==

Date: Thurs, Aug 21 2008 3:24 pm

From: "Edward Forrest Frank"

Lee,

I am interested in your opinion on the matter, so I was trying to

find out what you think rather than demanding that my opinion be

accepted.

The Ohio Report http://ohioline.osu.edu/rb1191/1191_1.html

and http://ohioline.osu.edu/rb1191/index.html

Reads:

"The taxonomy/identity of the Abies species in the eastern

United States and Canada has been confusing. Taxonomists have

traditionally recognized two species as being native to eastern

North America. Balsam fir (Abies balsamea (L.) Mill.) has an

extensive and more or less continuous natural range through Canada

and southward into Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, New York, and

northern Pennsylvania, with disjunct distribution through central

Pennsylvania and northern West Virginia and Virginia, while Fraser

fir (Abies fraseri (Pursh) Poir.) occurs only at higher elevations

in the mountains of southwestern Virginia, eastern Tennessee, and

western North Carolina (Figure 1). The most prominent taxonomic

feature used to distinguish between balsam and Fraser fir has been

the relative length of the cone scales and bracts. For balsam fir,

the bract is much shorter than and is fully enclosed within the cone

scale, while in Fraser fir the bract is much longer than the cone

scale and is exserted from the cone and reflexed downward. Attempts

have also been made to differentiate between these two species on

the basis of numbers of lines of stomata on the leaves and internal

leaf anatomy, but individual variations make interpretations using

those characteristics uncertain.

Some taxonomists have recognized two varieties of balsam fir, A.

balsamea (L.) Mill. var. balsamea, the "typical" balsam

fir and a "bracted" variety, A. balsamea (L.) Mill. var.

phanerolepis Fern., which is distinguished from var. balsamea on the

basis of the relative length of the bract and awn to length of the

cone scale and by a slight variation in cone size. The range of var.

phanerolepis has been identified as occurring within the range of

var. balsamea at higher elevations in the mountains of the

northeast, at lower elevations in Maine and the maritime provinces

of Canada, as well as the small, isolated stands in the mountains of

northern Virginia and West Virginia (Perry 1931, Fernald 1950,

Little 1953).

Classification of the small populations of fir at higher elevations

in northern West Virginia and Virginia (Figure 1) has been

particularly confusing. Trees from those populations have cones

similar to balsam fir as well as trees with exserted and reflexed

bracts characteristic of Fraser fir and intermediate-appearing forms

(Figure 2). These populations have, at various times, been

identified as A. balsamea (Millspaugh 1892, Core 1934, Core 1940),

A. fraseri (Millspaugh 1913, Zon 1914, Brooks 1920, Fulling 1934,

Wyman 1943), and A. balsamea var. phanerolepis (Perry 1931, Fosberg

1941, Fernald 1950, Little 1953, Strausbaugh and Core 1964), while

Fulling (1936) and Core (1934) suggested that they might represent a

separate species, A. intermedia, which was of hybrid origin between

balsam and Fraser fir.

A number of studies have attempted to clarify the status of the

Abies species in eastern North America. Oosting and Billings (1951)

suggested that during the most recent glacial advance (Pleistocene),

spruce-fir forests extended from Canada, south along the Appalachian

Mountains to North Carolina and Tennessee, with a clinal pattern of

phenotypic variation within that range. Since the glacial retreat,

populations have become separated and have evolved to their present

phenotypic expressions. Mark (1958) proposed that as the climate

warmed, fir populations at lower elevations in the southern part of

the range were replaced by other species, leaving only isolated

stands at higher elevations. The gap between the A. balsamea and A.

fraseri populations prevented gene flow from the northern

populations, resulting in a reduction in the gene pool of A. fraseri

during the recent xerothermic period, with genes responsible for

phenotypes similar to A. balsamea being eliminated.

Myers and Bormann (1963) studied phenotypic variation in trees of A.

balsamea var. balsamea and A. balsamea var. phanerolepis in response

to altitudinal and geographic gradients in cone scale/bract ratios

to measure intergradation between the two varieties. Their studies

found a complete series of morphological forms connecting the two,

with two clines within the A. balsamea population - one from lower

to higher altitudes in the mountains of the northeastern United

States and one at lower altitudes from coastal regions toward the

interior of the continent. Based on their data, they questioned the

taxonomic validity of separation of A. balsamea into two varieties

and also suggested that A. balsamea and A. fraseri represent closely

related and recently separated populations. Studies by Robinson and

Thor (1969) and Thor and Barnett (1974) compared various

characteristics of trees from the "intermediate"

populations of fir growing in northern West Virginia and Virginia

with those of trees of Fraser fir from Virginia, North Carolina, and

Tennessee and balsam fir from Pennsylvania and New York. They

concluded that the "intermediate" populations were not of

hybrid origin but rather are relicts of a once continuous fir

population having clinal variation along a north-south gradient.

Thor and Barnett (1974) also proposed that only one species of Abies

be recognized in eastern North America, with three varieties: var.

balsamea, var. phanerolepis (including the northern Virginia and

West Virginia populations), and var. fraseri.

Studies by Clarkson and Fairbrothers (1970) using serological and

electrophoretic investigations of seed protein of trees also

concluded that A. balsamea var. balsamea and A. fraseri are closely

related and recently separated taxa and that A. balsamea var.

phanerolepis (from the mountains of northern West Virginia and

Virginia) is more closely related to A. balsamea than to A. fraseri

and is not of hybrid origin. Studies by Jacobs et al. (1983), using

electrophoretic study of seed proteins, came to similar conclusions;

their study also found that electrophoretic patterns for seed of

"bracted" sources from Canaan Valley, West Virginia, and

Mt. Desert Island, Maine, were identical. "

This is the sum of the genetic information I have found on the

internet, and as you can see much of it is older data. There may be

more recent findings than these in the literature. The bulletin was

published in 1999.

Edward Frank

Literature Cited

Brooks, A. B. 1920. West Virginia trees. West Virginia University.

Agr. Exp. Sta. Bulletin 175. 242 p.

Brown, J. H. 1983. A "new" fir for Ohio Christmas tree

plantings? Ohio Report. 68(4):51-54.

Brown, J. H. 1998. Bud break and frost injury on three

sources/varieties of balsam fir. Christmas Trees. 26(2):24-27, 29.

Brown, J. H. 1998. Nitrogen fertilization of a Canaan Valley seed

source of balsam fir. The Ohio State University. Ohio Agricultural

Research and Development Center. Special Circular 159. 14 p.

Brown, J. H. 1999. 1998 update: bud break and frost injury on three

sources/varieties of balsam fir. Christmas Trees. 27(3):6, 8, 10.

Clarkson, R. B. and D. E. Fairbrothers. 1970. A serological and

electrophoretic investigation of eastern North America Abies (Pinacea).

Taxon. 19(5):720-727.

Core, E. L. 1934. The blister pine in West Virginia. Torreya.

34:92-93.

Core, E. L. 1940. New plant records for West Virginia. Torreya.

40:5-9.

Fernald, M. L. 1909. A new variety of Abies balsamea. Rhodora.

11:201-203.

Fernald, M. L. 1950. Gray's manual of botany. 8th Ed. American Book

Co., New York. 1,632 p.

Fosberg, F. R. 1941. Observations of Virginia plants. Part I.

Virginia Jour. Sci. 2:106.

Fulling, E. H. 1934. Identification, by leaf structure, of the

species of Abies cultivated in the United States. Bull. Torrey Bot.

Club. 61:497-524.

Fulling, E. H. 1936. Abies intermedia, the Blue Ridge fir, a new

species. Castanea. 91-94.

Jacobs, B. F., C. R. Werth, and S. I. Guttman. 1984. Genetic

relationships in Abies (fir) of eastern United States: an

electrophoretic study. Canadian Jour. Bot. 62:609-616.

Little, E. L., Jr. 1953. Checklist of native and naturalized trees

in the United States. USDA. Handbook 41. 472 p.

Little, E. L., Jr. 1971. Atlas of United States trees. USDA. Forest

Service Misc. Pub. 1146. Maps 2-N, 2-E, 4-E.

Mark, A. G. 1958. The ecology of the Southern Appalachian grass

balds. Ecol. Monographs. 28:293-336.

Millspaugh, C. F. 1892. Preliminary catalogue of the flora of West

Virginia. West Virginia University. Agr. Exp. Sta. Bulletin 24. 224

p.

Millspaugh, C. F. 1913. The living flora of West Virginia. West

Virginia Geolog. Survey. 5(A). 389 p.

Myers, O., Jr. and F. H. Bormann. 1963. Phenotypic variation in

Abies balsamea in response to altitudinal and geographic gradients.

Ecology. 44:429-436,

Oosting, H. J. and W. E. Billings. 1951. A comparison of virgin

spruce-fir forests in the northern and southern Appalachian system.

Ecology. 32:84-103.

Perry, L. M. 1931. Contributions from the Gray Herbarium of Harvard

University. No. XCIV. Rhodora. 33:105-126.

Robinson, J. F. and E. Thor. 1969. Natural variation in Abies of the

Southern Appalachians. For. Sci. 15:238-245.

Strausbaugh, P. D. and E. L. Core. 1964. Flora of West Virginia

(Part IV): 861-1075. West Virginia University. Bulletin Series 65,

No. 3-2.

Thor, E. and P. E. Barnett. 1974. Taxonomy of Abies in the Southern

Appalachians: variation in balsam monoterpenes and wood properties.

For. Sci. 20:32-40.

Wyman, D. 1943. A simple foliage key to the firs. Arnoldia. 3:65-71.

Zon, R. 1914. Balsam fir. USDA. Forest Service Bulletin 55. 68 p.

==============================================================================

TOPIC: Abies balsamea - a southern disjunct populatiom - sort of

http://groups.google.com/group/entstrees/browse_thread/thread/55d5a418079c1999?hl=en

==============================================================================

== 1 of 4 ==

Date: Fri, Aug 22 2008 6:09 am

From: ERNEST.OSTUNO@noaa.gov

Ed, Lee,

Here's a reference that mentions a continuous post-glacial presence

of

Balsam Fir at the Bear Meadows site in central PA :

MD Abrams, CA Copenheaver, BA Black, and S VanDeGevel. 2001.

Dendroecology and climatic impacts for a relict, old-growth, bog

forest in the Ridge and Valley Province of central Pennsylvania,

USA.

Canadian Journal of Botany 79:58-69.

Here's the abstract:

http://rparticle.web-p.cisti.nrc.ca/rparticle/AbstractTemplateServlet?journal=cjb&volume=79&year=&issue=&msno=b00-145&calyLang=eng

Quote:

"Most Abies balsamea trees have reached their pathological age

of

50-85 years and have active Armillaria root rot, insect

infestations,

and very poorly developed crowns. These symptoms or severe growth

declines are not present in Picea mariana. It appears that the 10

000

year history of Abies balsamea presence at Bear Meadows will end

soon,

with no opportunity to reestablish itself because of the lack of a

local seed source."

Ernie

== 2 of 4 ==

Date: Fri, Aug 22 2008 3:30 pm

From: Lee Frelich

Ed, Ernie:

To see whether the quote by Abrams et al regarding presence of fir

for the

last 10,000 years is true, I would have to see the paper they cite

from

Pennsylvania Academy of sciences:

Kovar, A.J. 1965. Pollen analysis of the Bear Meadows bog central

Pennsylvania. PA Academy of Sciences Publication No. 38., pp 16-24.

The academy does not have old publications on their website, so I

can't

check it, and I wouldn't take the authors of the Abrams et al paper

word

for it either.

I can summarize what I think at this point by saying that for the

most

part, fir disappeared during the mid-Holocene and then came back in

the

last few thousand years over most of the landscape, although there

is a

chance that some survived in bogs or high elevations. Its likely

that the

southward march of fir from the main range swamped local expansion.

This

pattern was much more exaggerated in Minnesota because climate

changes are

all exaggerated due to being in the center of the continent. I don't

think

there is enough genetic information yet to reconstruct what happened

from

that type of evidence (such as Jason McLachlan of Notre Dame

University has

done for beech).

Lee

== 3 of 4 ==

Date: Fri, Aug 22 2008 5:12 pm

From: DON BERTOLETTE

Lee/Ed/Ernie-

As a former GIS person, I recall a great resource for those wanting

to check known species locations...notice that it was listed in the

bibliography below, but am supplying a link for it, including balsam

fir:

http://esp.cr.usgs.gov/data/atlas/little/

-DonRB

== 4 of 4 ==

Date: Fri, Aug 22 2008 9:29 pm

From: "Edward Forrest Frank"

Lee,

Thanks for the discussion on this subject. I had always heard of

these populations being referred to as remnant populations from the

ice ages. Now I see that it may not be that straight forward. I had

been thinking the WV an VA populations were likely remnants because

there had been some time for genetic differentiation. But by my own

arguments, if they were part of a once advancing front, this also

could have led to the genetic difference. If they were part of a

limited population as part of an advancing front, with a low initial

genetic diversity, then any minor variant, expression of a uncommon

genetic trait, or even a favorable mutation could more quickly

spread among the entire population than would be possible for a

larger population with a higher initial diversity. I am not sure

what to think about the issue now, but the discussion has been very

instructive. As you said the genetic character of the populations,

"could be consistent with a recent founder effect or loss of

genes through long term isolation."

You mention the idea of "long distance dispersal by plants

during migration." Perhaps that is what is needed as with

global warming the plant climate ranges could be moving northward

faster than the plant can follow. The presence of some long distance

dispersal mechanism might be needed for the trees to just keep up.

Ed

|