Spent a very nice day with Ed Frank and Randy Brown at the Holden

Arboretum

in Kirtland Hills, Ohio. The weather was perfect, in the low 70's,

and we

had a guided tour by Holden Arboretum staff, visiting the Stebbin's

Gulch

area. Ed and Randy, I'm sure, will be posting detailed

measurements--here

are a couple of photos: Randy under the huge burl of a chestnut oak,

Ed next

to a very nice sugar maple.

[Edward Frank, April 20, 2009]

Holden Arboretum, Ohio

On Saturday April 18, 2009 I met Randy

Brown, Steve Galehouse, and his son Mitch Galehouse at Holden

Arboretum in Lake and Geauga Counties in northeastern Ohio.

http://www.holdenarb.org/home/

I had corresponded with Steve and Randy before but had

not met either of them previously.

The trip to the arboretum was organized by Randy Brown.

I want to thank him for the opportunity to participate.

We met Michael Watson, Ethan Johnson, and Dawn Gerlica

from the arboretum the visitor’s center.

They were to be the guides on our trip.

Steve had been to the arboretum several times before as

he is from the Cleveland area.

I had visited Holden once previously on a trip with Carl

Harting in September 2007

http://www.nativetreesociety.org/fieldtrips/ohio/holden/holden_arboretum.htm

“The

Holden Arboretum owns over 3,600 acres, which includes the

recent Roudebush parcel purchase of 90 acres. Of that,

approximately 3,100 acres are natural areas. Approximately 85

percent of Holden’s natural areas are woodland; 12 percent

meadows; and the remaining three percent are wetlands, streams,

rivers, ponds and lakes.”

http://www.holdenarb.org/education/conservation.asp

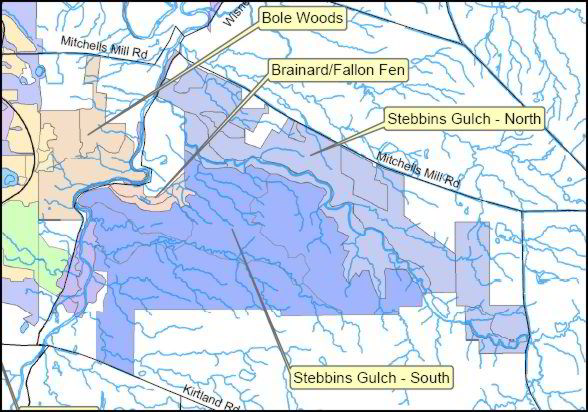

“For the sake of

management purposes, The Holden Arboretum has been organized

into 14 natural areas. Some of these natural areas are well

known, such as Pierson Creek Valley, Bole Woods, Carver’s Pond,

Little Mountain, and Stebbins’ Gulch; and others are less well

known and visited. Some of Holden natural areas are open to the

public while others are closed to the public and accessible only

with a guide or permit.”

A map of these areas and the Arboretum properties can

be downloaded here:

http://www.holdenarb.org/education/documents/HoldensNaturalAreas.pdf

On this trip we were going to visit an area

known as Stebbin’s Gulch.

This area is described on the website:

·

Stebbins Gulch, North – A National

Natural Landmark that is an excellent example of a NE Ohio

bedrock ravine system. Guided hikes provide a rigorous and rare

natural and geologic history experience in a cold water stream

ravine. Along the bluffs of Stebbins Gulch is one of the best

remaining hemlock-northern hardwood forest remnants in Ohio.

·

Stebbins Gulch,

South – This 800-acre natural area is Holden’s largest unbroken

mature forest and protects the associated diversity of flora and

fauna of an old-growth forest. Access is limited to stewardship,

research or guided hikes.

Geology and Topography

The northern edge of the Allegheny Plateau

in this portion of Ohio is marked by the Portage Escarpment.

The escarpment parallels the shoreline of Lake Erie and

climbs from around 780 feet at its base to almost 1000 feet at

its crest. North of

the escarpment is the narrow Lake Plain that extends to the

shore of Lake Erie.

The area to the south of the escarpment consists of a plateau of

Mississippian Age bedrock (359 – 318 million years ago).

This bedrock was repeatedly eroded by Pleistocene

glaciations during the last million years.

Outwash and moraines formed from the retreat of the last

glaciation episode has filled depressions in the landscape

leaving a gently rolling, poorly drained landscape.

Streams flowing across this plateau have eroded deeply

incised, steep sided channels into the bedrock and drain

northward to the Lake Erie.

Stebbins

Gulch is one of many incised stream valleys located in this area

of Ohio. It flows

from east to west and empties into the eastern Branch of the

Chagrin River, which in turn drains the entire area and feeds

into Lake Erie a few miles to the north.

Elevations range from 750 feet in the Chagrin River

Valley to just over 1200 feet in the surrounding hills.

In Stebbins Gulch itself the

walls of the ravine are composed of Mississippian Berea

sandstone underlain by Bedford shales and thin interbedded

sandstone.

The stream itself drops within the arboretum properties about 60

feet flowing over a series of small falls and rapids which have

developed where shales have eroded beneath more resistant

sandstone beds.

This bedding is clearly exhibited in the walls of the gulch.

Vertical faced ledges of sandstone are interspersed with

sloping segments of eroded shale.

Near the top of the cliffs a series of drip areas and

springs have formed immediately below the sandstone caprock

where the downward seeping water meets the relatively

impermeable shale below.

Stebbin’s Gulch North

After meeting in the lobby of the Visitors

Center, we gathered out gear and carpooled to the first stop of

the day –Stebbin’s Gulch North.

I was

looking forward to this area because it was the location of some

very old chestnut oaks. Dr.

Ed Cook collected a series of 24 cores in 1983 from somewhere in

the Stebbin’s Gulch area, very likely these same trees. The

oldest specimen dated from 1612 and likely is still alive today,

if so it would be 397 years old.

http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo/metadata/noaa-tree-3033.html

So this was something that promised to be worth seeing.

View on

edge of Stebbin's Gulch ravine on north side

On this trip Dawn brought her infant son

Aidan along. He is

about a year-and-a-half years old now.

On my last trip he was at minus 2.5 months old.

We had a short walk to the edge of the ravine.

The cliff plunged almost straight down.

This is one of the reasons why they don’t want visitors

to walk this area unguided.

From this point we turned left and walked upstream along

an old trail along the edge of the ravine.

Soon we were encountering large, gnarled, old looking,

chestnut oaks (Quercus

prinus; syn. Quercus montana).

In addition were many large towering, American beech.

Chestnut Oak, 11.5 feet girth,

83 feet tall

The understory included a number of species

most prominently were numerous smaller eastern hemlock.

We walked from tree to tree.

The oaks were covered by thick ridged bark.

The stems were fat and bent.

In the canopy there were thick, heavy, stubby, branches

that had been bent and broken by years of weather and wind.

Randy

Brown and Steve Galehouse with large burl in Chestnut oak.

The tree was 9' 11" in girth and 93 feet tall.

Present on several chestnut oaks were giant

burls, some bigger around than the tree itself. These were the

biggest I have seen on any eastern tree.

I wondered how they formed.

This glossary

http://oak.arch.utas.edu.au/glossary/view_glossarylist.asp?term=B

defines a burl

as:

“A hard, woody outgrowth on a

tree, more or less rounded in form, usually resulting from the

entwined growth of a cluster of buds. Such burls are the source

of the highly figured burl veneers used for purely ornamental

purposes.”

Another site

http://www.newton.dep.anl.gov/askasci/bot00/bot00682.htm

includes this comment:

“They

are basically benign tree tumors.

They occur when a twig bud fails to

grow normally, differentiating into the tissues needed for

forming a limb,

and instead just multiplies and multiplies and multiplies its

bud cells. That's how you get the round growth with an irregular

grain structure.”

Along the rim of the valley the trees are

not only exposed to winds along their tops but are also subject

to winds along the side open to the valley.

Winds are funneled down valleys have an big impact on the

trees growing along their rims. Dr. Tom Diggins has shown in

Zoar Valley, NY that there is a preferred orientation of course

woody debris aligned with the valley walls as a result of these

types of winds. At

this site and at other similar sites you can see the branches on

the valley side are often more wind damaged than other branches

on the tree. The

same can be said of the other trees growing along the rim, a

bent and broken black gum comes to mind from this site.

However none of the trees here along the rim showed this

character quite as much as the chestnut oaks, perhaps because of

their age and the years of exposure to the wind, perhaps because

they have survived rather than died from wind events that might

have killed other trees.

They certainly were impressive.

The trees on the edge of ravine also face other

challenges. They

often are found leaning inward and struggling to stay upright.

The soil and rocks beneath them tends to slowly creep

downward or be washed into the valley below pulling the roots

and trees along.

There were smaller beech along the rim a

along the walls of the canyon, but the largest ones were set

back from the edge of the cliff by a hundred feet or more. Many

were eight to ten feet in girth, some larger.

They typically reached heights from between 100 feet tall

with some reaching into the mid- one-teens.

With additional time and dedicated searching a few

taller heights might be discovered among the tops.

It is hard to tell the age of American beech.

It has smooth bark and does not develop the heavy ridges

or platy textures of many tree species.

These have broad spreading crowns with large limbs.

They certainly are very mature trees.

I would not be surprised if they are 150 years old or

older, but still they could be much younger as well.

One of the curious characteristics of the

site was the hemlocks.

The website blurb has described it as a remnant

hemlock-northern hardwood forest.

There were a number of larger hemlock trees but most were

small and seemed to be young trees.

They did not have any of the gnarled characteristics or

heavy bark seen on older hemlock specimens.

Perhaps they are now, ironically spreading out because of

the loss of other species in the canopy.

I do not know what species they might have been replacing

or why they made up such a large percentage of the younger

trees.

Patterns on red maple bark

The last trees we visited on the north side

of the gulch were some butternuts.

Dawn had told us that there were four butternuts.

One had died and decayed away.

A second was found leaning over on another tree and dead.

Two were hanging in there barely as they were succumbing

to blight. It was

sort of a down note at this point.

The trees had not leafed out yet, and they

were few herbaceous plants poking out of the ground yet.

At the cars a touch of green in the canopy of the trees

bordering the parking area caught our eye.

It turned out to be the

catkins of a stand of bigtooth aspen.

This was a quick tour of a small section of Stebbin’s

Gulch North, but I think of it more as preliminary scouting for

a future trip.

Stebbin’s Gulch South

Next we headed to the area designated

Stebbins Gulch South.

We pulled into a parking area near the west end of the

800 acres natural area.

In the parking area was massive red oak.

We measured it to be 13’ 4” in girth and 114.2 feet tall.

My initial shot upward reached about this number, but

further exploration could not push it to the over 120 as I had

hoped. The

character of this area of the site was entirely different from

the canyon edge area we visited on the north side of the gulch.

Here we were on top of the plateau itself.

The area was crossed by a series of horse trails. The

landscape was relatively flat with gently rolling hills and

depressions. This

area was underlain by clay rich glacial till and generally

poorly drained.

There was a good diversity of trees in the area with sugar

maples, red oak, and beech being the predominant species.

Tuliptree and white ash were also fairly common.

In the area immediately by the parking lot the trees

tended to be smaller, suggesting the possibility that the area

may have been logged at some time in the past, but there were no

overt signs of any logging.

Our guides wanted to show us an area of some big black

cherry, oak, and sugar maples.

After a short hike we were finding more large oaks and

other large tree.

Adjacent to the path was a black cherry, 11’ 2.5”

in girth, and 117.9 feet

tall. This was the

largest of several big black cherries in the immediate area.

Randy Brown and large black

cherry, 11' 2.5" girth, 117.9 feet tall

From left to right Michael Watson,

Ethan Johnson, and Dawn Gerlica (Aidan in backpack)

Shortly thereafter, with Aidan being tired

from being carried in a backpack through the woods, the people

from the arboretum left us on our own.

Steve, Randy, Mitch and I were off exploring.

Steve and I measured an impressive sugar maple 10’ 4” in

girth and 117 feet tall (see Steve Galehouse's photo in previous

post). It was large

in size and perfect in form.

We scattered across the area and measured.

Randy measured some large white ash trees.

I measured a tuliptree at 136.9 feet tall, only later to

be outdone by Steve and Randy with a 142.5 foot tall, 10 foot

girth specimen. Near the

tall Tuliptree was another large sugar maple with very rough

looking bark. We

were unsure of the identification until we walked over

to the tree and looked

at it in detail from

close up (the presence of sugar maple leaves under the tree

helped me). Another

tall species found was a 122.6 foot tall American beech.

It was located in the bottom of one of many shallow

depressions across the plateau.

Sugar Maple with rough bark

After measuring for awhile we got together

again and compared notes on what we had found and what species

we had measured. At

the time we had six species over 100 feet tall, but not many of

other trees present in the area.

We decided to try to finish out the ten species Rucker

Index and explore for other species.

This is an area where I am comparatively weak.

I am not good at identifying trees by their bark and form

alone. I can do

some well, but am not confident of my identification of others.

Randy and Steve are both excellent at this.

On the hilltops hemlock was absent, but smaller specimens

began to appear as one headed down slope to some of the small

streams in the area.

The ones higher on the slope were smaller, but eventually

we found some bigger trees

the tallest was just 108.9 feet tall – but hey it was

another species over 100 feet.

Flowers

White pine was all but absent from the

area. We sighted a

pair just off the trail to the north as we were walking in, and

Steve saw one across a small stream valley to the south.

These were the only ones we found in the entire area.

I have corresponded with Michael Watson, one of the

Holden people on the trip.

He writes:

“At Holden, I associate

white pine with our Little Mountain property. Soils up

there are shallow and pretty dry. Acidic, too I believe.

In South Stebbins the soils are richer and wetter (as you saw

from the condition of the horse trails). So my thought is

that the lack of white pines in South Stebbins is at least in

part due to the soils. As I understand it, Beech-Maple

communities are generally found on rich, moist soils - so

perhaps in those conditions they simply out-compete the pines. “

There are nice

stands of pines on Little Mountain.

Carl and I visited the site on the last trip.

The lack of white pines in the Stebbin’s Gulch South

section we visited really strikes me as they never were present,

rather than they were removed.

On the way out we measured the white pine Steve sighted

earlier. I got a

good shot from across the small stream valley and measured a

height of 131.4 feet.

Randy scrambled down and up to the tree to get a girth

measurement of 10.0 feet.

Another odd character of this side of the

gulch was the absence of chestnut oak and white oak.

We found no chestnut oak in the area we visited and only

one white oak tree.

I would have expected these oak species to have been present

here. We did not

get to the rim of the gulch itself on the south side.

I am curious how the character of the forest might change

along the rim, if it would more resemble the tree assemblage

found on our brief excursion on the north side.

Last year's puffballs growing on an old log

Altogether I have measurements (actually

Steve and I) have measurements for 18 species of trees, twelve

of them were over 100 feet.

Randy measured white ash and sycamore each over 100 feet.

The species I have result in a Rucker Index of 117.17.

With the addition of Randy’s data that will likely

increase by a foot or two. During

this visit we only saw a small part of the 800 acre Stebbin’s

Gulch South section.

With more exploration I am sure many taller trees could

be found. It was

great to meet Randy, Steve, ad Mitch and I had a great time.

I came away with a sunburn and good memories.

What's Next?

There is still large areas of the arboretum

to visit. Many areas already scouted need to be have time

spent in them to properly document the trees present. Carl

and I measured a large black walnut on the first trip at 126.9

feet and Carl was not sure he found the actual top. It

needs to be remesured. Dawn told me of a fat red maple

that had been tapped with eight buckets at sugaring time.

She says it is a single stem and the biggest red maple she has

seen. It would be worthwhile to hike up the bottom of

Stebbin's Gulch itself, not to mention further explorations of

the plateaus on each side of the canyon. Corning Woods and

Bole Woods contain old growth that needs to be documented or

better documented. There is still much to do at the

arboretum.

Here is a spreadsheet of measurement data. I will post a

revised list later with randy's measurements included.

|

Holden

Arboretum |

April 18, 2009 |

Randy Brown, Steve

Galehouse, Edward Frank and Mitch Galehouse |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tree (common name) |

species |

Height (ft) |

Girth

(ft) |

Latitude |

Longitude |

Elevation GPS (ft) |

Comments |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stebbin's Gulch North |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chestnut oak |

Quercus montana |

83 |

11.75 |

41' 36.459 |

-81'

16.280 |

1088 |

largest, leaning |

|

|

Chestnut oak |

Quercus montana |

93 |

9'

1" |

41' 36.425 |

-81' 16.186 |

1150 |

big burl |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stebbin's Gulch South |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tuliptree |

Liriodendron tulipifera |

136.93 |

10.5 |

41' 36.213 |

-81' 18.561 |

|

|

|

|

Black Cherry |

Prunus serotina |

117.9 |

11'

2.5" |

41' 36.192 |

-81' 18.511 |

1170 |

cherry along trail |

|

|

Sugar Maple |

Acer saccharum |

117 |

10'

4" |

41' 36.189 |

-81' 16.447 |

|

|

|

|

Black Cherry |

Prunus serotina |

111.86 |

9'

10" |

41' 36.174 |

-81' 16.405 |

|

behind fallen one |

|

|

Red Oak |

Quercus rubra |

109.79 |

14 |

41' 36.215 |

-81' 18.584 |

|

|

|

|

American Beech |

Fagus grqandifolia |

122.57 |

7'

7" |

|

|

|

near red oak above |

|

|

Hemlock |

Tsuga canadiensis |

44 |

3.0' |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Black Cherry |

Prunus serotina |

110.83 |

8'

8" |

|

|

|

one with grape vine |

|

|

Red Maple |

Acer rubrum |

99.3 |

6.0' |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hemlock |

Tsuga canadiensis |

108.91 |

4'

4" |

|

|

|

tall top |

|

|

Cucumber Magnolia |

Magnolia acuminata |

107 |

11'

3.5" |

41' 36.116 |

-81' 16.521 |

|

near hemlock above |

|

|

Hemlock |

Tsuga canadiensis |

104.23 |

6'

3" |

41' 36.118 |

-81' 16.532 |

1127 |

|

|

|

Black Gum |

Nyssa sylvatica |

84 |

7'

6" |

41' 36.118 |

-81' 16.544 |

1088 |

|

|

|

Basswood |

Tilia americana |

103.89 |

7'

5" |

41' 36.176 |

-81' 16.448 |

1209 |

along blue trail |

|

|

Basswood |

Tilia americana |

89 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sugar Maple |

Acer saccharum |

111.74 |

9'

1" |

41' 36.240 |

-81' 16.655 |

|

very rough bark |

|

|

Tuliptree |

Liriodendron tulipifera |

142.5 |

9'

5" |

|

|

|

below sugar maple |

|

|

Slippery Elm |

Ulmus fulva |

? |

6'

3.5" |

41' 36.224 |

-81' 16.625 |

|

along trail |

|

|

Black Walnut |

Juglans nigra |

106.43 |

7'

5" |

41' 36.265 |

-81' 16.745 |

1052 |

along trail |

|

|

Shagbark Hickory |

Carya ovata |

102 |

7'

8.5" |

41' 36.255 |

-81' 16.759 |

|

along trail |

|

|

White Pine |

Pinus strobus |

131.3 |

10.0' |

|

|

|

across stream up bank |

|

|

White oak |

Quercus alba |

100.5 |

6'

6" |

41' 36.189 |

-81' 16.946 |

|

|

|

|

Red Oak |

Quercus rubra |

104 |

7'

7" |

41' 36.198 |

-81'

16.943 |

1013 |

|

|

|

Sassafras |

Sassifras albidum |

74 |

3'

4.4" |

41' 36.378 |

-81' 17.250 |

|

three single stems |

|

|

Norway Spruce |

Picea abies |

84.7 |

5'

8" |

|

|

|

beside sassafras |

|

|

Red Oak |

Quercus rubra |

114.24 |

13'

4" |

41' 36.370 |

-81' 17.367 |

|

red oak in parking area |

|

|

Yellow Birch |

Betula alleganiensis |

70 |

4'

7" |

41' 36.373 |

-81' 17.351 |

|

near parking area |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tuliptree |

Liriodendron tulipifera |

142.5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

White Pine |

Pinus strobus |

131.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

American Beech |

Fagus grqandifolia |

122.57 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Black Cherry |

Prunus serotina |

117.9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sugar Maple |

Acer saccharum |

117 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Red Oak |

Quercus rubra |

114.24 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hemlock |

Tsuga canadiensis |

108.91 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cucumber Magnolia |

Magnolia acuminata |

107 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Black Walnut |

Juglans nigra |

106.43 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Basswood |

Tilia americana |

103.89 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rucker Index |

117.174 |