|

Hi All,

In 1892, the New York State legislature established the Adirondack

Park, which now encompasses nearly six million acres and occupies

most

of northern New York.

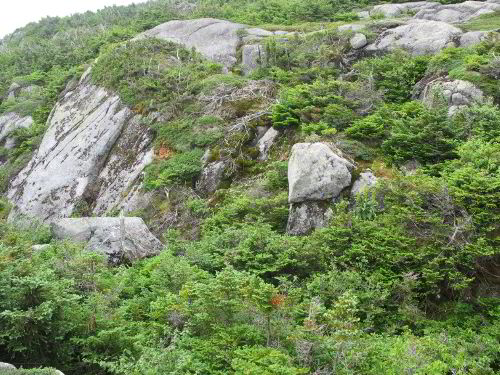

Gothics. The Great Range Trail is visible as thread of

exposed rock on the ridge in the center of the photograph.

The park includes approximately 2.5

million

acres of Forest Preserve, designated "forever wild", and

most of the

Adirondack Mountains, a still rising section of the Canadian Shield

(http://www.apa.state.ny.us/About_park/index.html).

The low relief of

the mountain range's southern and western sections, often just a few

hundred feet, gives little indication of the High Peaks region's

ruggedness. There, streams cascade through gorges, sheer

cliffs

plunge into glacial lakes, the peaks extend up into climates too

harsh

for trees, and landslides and avalanches scar the slopes.

Those

features combined with the close proximity to New York City have

made

the region a mecca for outdoor recreationists, and lead to the

development of an extensive trail network.

A typical steep stretch of the Great Range Trail

Lee Davis, another grad student at SUNY-ESF, and I recently took a

three day trip through the heart of the region focusing on the

higher

peaks. We started at slightly over 2000' elevation in the flat

lands

south of Lake Placid, and briefly passed through an old red pine

plantation with wild sarsaparilla dominated herb layer.

However,

following a small stream towards the larger mountains we soon

reached

a gentle, north-facing slope where the logging operations of the

late

1800's appeared to have removed only red spruce, which along with

white pine was the most prized timber species of the time.

Sugar

maples, some approaching three feet in diameter, formed most of the

overstory along with beech, most of the larger ones showing damage

from beech bark disease, and yellow birch. Sugar maple also

dominated

the understory although striped maple and beech sprouts were also

common.

Mount Colden behind Marcy Dam Pond. |

Passing through a shallow gap brought us to the slopes

surrounding Marcy Dam where more intense logging activity had

dramatically altered the forest's composition. The dense

canopy

comprised paper birch and balsam fir, except along the stream banks

where yellow birch and mountain ash added diversity. In that

forest,

paper birch saplings were rare, but balsam fir and red spruce formed

a

well developed understory over bunchberry, goldthread, starflower,

and

whorled wood aster.

An opening in the balsam fir forest next to Lake Tear of

the Clouds at approximately 4300' elevation.

Bunchberry blooms in the lower right, and the large leaves

just above them belong to hellebore. |

Mountain sandwort, one of the common species in the alpine

zone. |

We ascended from Marcy Dam towards Avalanche Pass, our gateway to

the

interior of the High Peaks region. Unlike the nearby Green

Mountains

or the higher ranges of the southern Appalachians, each of which

consists of essentially one large, undulating ridge with descending

spur ridges, the High Peaks region contains several distinct

northeast-southwest oriented ridges with occasional cross-linking

ridges, more like New Hampshire's White Mountains. Avalanche

Pass

separates the McIntyre Range with Algonquin Peak, the second highest

peak in NY at 5114', from the Great Range with Mount Marcy, the

highest mountain in NY at 5344'. At the pass, we also left

behind the

signs of past logging disturbance, but the forest was far from

undisturbed. In 1999 several acres of forest and soil on one

side of

the pass slipped off the mountain side and piled small paper birch

and

conifer trunks over ten feet high in the pass. On either side

of the

landslide's base, northern white cedar cling to low cliffs and red

spruce, balsam fir, and paper birch dominate the surrounding forest.

Avalanche Lake. Photograph by Lee Davis |

Meadow rue blooming beside Avalanche Lake. |

Continuing through the pass brought us to the larger expanses of

rock

bordering Avalanche Lake where a 200' high rock wall rises directly

out of the lake. The trail weaves around the lake by

traversing the

forested talus slope that separates the opposite shore from the

higher

cliffs of Avalanche Mountain. The more tame upper and lower

margins

of the lake provided open habitat for white meadowsweet, leatherleaf,

meadow rue, sedges and grasses.

Eriophorum vaginatum var spissum: Cotton sedge thrives

around the

edges of high elevation bogs.

After reentering the forest at the downstream end of Avalanche Lake,

species composition varied little as we followed a small stream to

Lake Colden, skirted the edge of the lake, and gained elevation

along

the upper reaches of the Opalescent River. Bunchberry, whorled

wood

aster, northern beech fern and many bryophytes also thrived in the

shade provided by balsam fir and smaller numbers of red spruce,

paper

birch, and near the waterways, northern white cedar.

Opalescent River: Rapids on the upper reaches of the

Opalescent River.

The

Opalescent

River cascades over and sluices through highly fractured

bedrock,

and

the rock exposed along its edges provides the cedars with

habitat

sharing many features with that of the cliff dwelling cedars seen

around Avalanche Lake. However, cedars also grow at a short

distance

from the river and along smaller streams not on bedrock. At

around

3300' elevation, the gradient of the Opalescent River drops

dramatically, the water courses around boulders rather than bedrock,

and white cedar vanishes from the banks. Instead, mountain ash

and

shrubs including a viburnum, alder, Bartram's serviceberry, and

round-leaved dogwood grow scattered along the stream bank amongst

the

three dominant tree species: balsam fir, red spruce, and paper

birch.

In that upper hanging valley, draining the slopes of Mount

Colden and

Mount Marcy, most of the mature individuals of those canopy species

had died within recent decades leaving a dense regenerating forest

of

saplings.

Rhizocarpon geographicum: The yellow crustose lichen

is Rhizocarpon

geographicum, one of the dominant species in the alpine zone. |

Saddleback with multiple avalanche scars visible on the

right side. |

Above the relatively sheltered slopes along the upper Opalescent

River, wind and cold take their toll on both forest diversity and

forest stature. By 4300' elevation, trees over 40' tall were

scarce,

as was red spruce, and paper birch persisted only as scattered small

individuals. The climate and balsam fir canopy favored

bunchberry,

bryophytes, and to a less extent northern beech fern. As we

continued

toward the top of Mount Marcy, the canopy height gradually declined

to

about 15', but the firs remained straight.

The alpine zone on top of Mount Marcy. |

Krummholz on Mount Marcy. |

That stunted forest

transitioned on the upper side into krummholz, the twisted

and

dwarfed

community produced where harsh alpine conditions approach

the limits

of trees' tolerances. The krummholz's dense canopy formed

primarily

from interlocking branches of balsam firs less than five feet tall,

but spruce, probably black spruce, dominated some patches and resin

birch, paper birch, and mountain ash, probably showy mountain ash,

grew scattered amongst the conifers. On the summit of Mount

Marcy,

the severe conditions forced the krummholz to give way to an alpine

community, home to many species rare in the state. Most of the

community consisted of crustose lichens, especially Rhizocarpon

geographicum, covering the bare, windswept rock of the summit, but

plants could survive where boulders or rock ledges provided shelter

or

crevices allowed soil to accumulate. Most of the alpine plants

are

fairly unobtrusive since they adopt low, compact growth forms to

stay

close to the relatively warm ground and minimize wind exposure, but

Mountain sandwort and three toothed cinquefoil's flowers made them

conspicuous as we traversed the summit. Labrador tea, white

meadowsweet, and bog laurel, all species also occurring in wetlands,

also flowered in the interface between the krummholz and the alpine

zone, an area that also provided habitat for several shrubs

restricted

to the mountaintops.

The edge of a rock outcrop

From the summit of Marcy, we followed trails along the crest of the

Great Range and away from the steady stream of people intent on

reaching the state's highest point. The popularity of the

trails, the

easily eroded soils, and routing of trails straight up and down the

slopes have combined to reduce sections of trail to a series of

boulders; hence, hiking the trails often involves much more rock

hopping than walking. On the steepest peaks, the trails also

include

stretches on bedrock inclined up to 45 degrees (100%) to take hikers

form the deep gaps back up to the peaks. The peaks' rock

outcrops and

stunted vegetation permit broad views of the surrounding mountains

and

glimpses of the lakes nestled between them. Most of the higher

summits feature large areas of exposed light colored rock running

down

their slopes that contrast with the dark green of the surrounding

conifer forest. On a few peaks, long linear vegetated but not

forested streaks extend down from the rock outcrops, probably scars

from avalanches. On the forested slopes, the dominance of

balsam fir

is apparent in the sea of well-formed conical crowns pierced only by

scattered red spruce and interrupted by the lighter green domes of

paper birch.

A Cladonia and a darker unidentified lichen intermingle on

the edge of the

krummholz zone.

We started passing under more spruce and paper birch crowns as we

left

the spine of the Great Range and descended along Wolf Jaw Branch.

Many of the paper birch appeared fairly young, but the forest still

contained relatively large red spruce, around two feet dbh, that

would

have been targeted by loggers. Yellow birch were shorter than

the

spruce, but reached larger diameters, especially on broad gentle

slopes, which also supported the largest balsam firs we saw, around

75' tall. The lower canopy layers also changed as we reached

more

productive gentle topography with thickets of conifer saplings and

large colonies of bunchberry giving way to a sparser mix of conifer

saplings and striped maple and a thick layer of wood fern or

mountain

wood fern. As we continued down into warmer climates, conifer

abundance declined and sugar maple and yellow birch became the

dominant species; the latter were among the largest trees we saw on

the trip with diameters approaching three feet. Conifers

returned to

dominance after we crossed Johns Brook and began ascending Black

Brook

towards Klondike Notch, but yellow birch remained a major canopy

component and quaking aspen occurred in scattered groves.

Second growth paper birch dominated forest along Klondike Brook.

The forest changed dramatically after we passed through the notch.

Gentle topography, relatively productive soils, and easy access from

the flat lands south of Lake Placid, made the Klondike Brook

watershed

an obvious target for early logging operation. The disturbance

produced an opportunity for balsam fir and paper birch to dominate

the

west facing slopes at the upper end of the watershed and for paper

birch and smaller numbers of yellow birch to dominate most of the

gentle northeast facing slopes farther down the drainage.

Mountain

maple and striped maple form a relatively dense understory beneath

the

birches and either intermediate woodfern or mountain woodfern hide

the

forest floor. However, scattered herbs characteristic of

richer site

including red baneberry, rosy twisted stalk, and plantain leaved

sedge

grew amongst the ferns and sugar maple entered the overstory at

lower

elevations.

We left those hardwood and rich site species behind as we exited the

Klondike Brook watershed and completed our loop by traversing flat

lands covered in conifer plantations. The regular rows of red

pine

and Norway spruce would have made that final leg monotonous if a

beaver flow had not obliterated the abandoned trail we were

following.

Instead, we found ourselves wading through clumps of beaked

hazelnut,

scrambling through a balsam fir forest on an isolated steep-sided

ridge, and ducking through speckled alder thickets along Marcy

Brook.

Mushrooms growing beside the trail in a sugar maple and

yellow birch stand. They are probably waxy caps in the genus

Hygrocybe.

Throughout the trip, mushrooms added color to the forest floor.

By

far the most common were aminitas, russulas, and boletes, all very

common genera capable of forming mycorrhizae with spruce, fir, and

birch. Descriptions of birch in the region include both the

common

paper birch, which probably made up the second growth stands, and

mountain or heartleaf paper birch, which was probably common at high

elevations. Similarly, both American mountain-ash and showy

mountain

ash are known from the area, with the latter occurring more often at

high elevations (Ketchledge 1996). The largest mountain ash

were

American mountain-ash, and we measured three at 3'5.5" x 51.4',

3'0" x

54.3', and 2'6.5" x 55.4'. Those heights fall just short

of the

greatest confirmed height for the species, 56.1' for a tree in Great

Smoky Mountains National Park, and all three grow around 3000'

elevation. The transition between hardwood and conifer

dominance also

generally occurred between 3000' and 2500' elevation although balsam

fir, red spurce, and paper birch grew across all elevations.

Jess Riddle

Ketchledge, E H. 1996. Forest and Trees of the Adirondacks High

Peaks

Region. Adirondack Mountain Club. 166p.

== 3 of 3 ==

Date: Fri, Aug 15 2008 1:00 pm

From: djluthringer@pennswoods.net

Jess,

Thanks for putting out your hike description. I've been wanting to

hike that

stretch for some time now. It is very nice to have a good

description of the

vegetation up there. While reading your note, it felt like I was

right there

walking it with you.

Dale

==============================================================================

TOPIC: Adirondack High Peaks

http://groups.google.com/group/entstrees/browse_thread/thread/8603682b7dd767b9?hl=en

==============================================================================

== 1 of 3 ==

Date: Sat, Aug 16 2008 5:31 am

From: ForestRuss@aol.com

Jess:

I think I hit most of the trails and peaks you traversed in the

early 1980s.

The one thing I remembered the most...aside from the incredibly

steep solid

granite face above avalanche lake was some of the large white cedars

along

the trail. I still have a round rock I got from diving deep into one

of the

plunge pools in the Opalescent River that seemed to have incredible

pot holes

all the way up the valley. It was some of the coldest water I ever

swam in

but the ice cold water was incredibly effective at dissipating the

black flies

and mosquitos....it seems like under water was the only place they

weren't.

The Krumholtz on Colden Peak blew me away, especially the incredibly

small

larch trees that were a foot tall and very, very old.

Russ

== 2 of 3 ==

Date: Sat, Aug 16 2008 7:54 am

From: Larry

Jess, Awesome report and great photos! Larry

== 3 of 3 ==

Date: Sat, Aug 16 2008 7:06 pm

From: JamesRobertSmith

I'm jealous!!! The Adirondacks are on my must-see-before-I-die list

of

wild places. I especially want to trek the high peaks. Maybe in two

years?

We should to to the South what NY has done with Adirondack Park. As

quickly as possible all rural and wild lands remaining in the South

should be off limits to further development. That's the only way

we're

going to save our forests and species, and preserve our rural

heritage.

To Hell with sub-divisions and shopping centers. Real estate

developers should all be sent straight to Hell.

== 2 of 2 ==

Date: Sun, Aug 17 2008 5:15 am

From: dbhguru@comcast.net

James,

The Adirondacks are my wife's favorite place. I too am bullish on

the Dacks, mainly because of the huge area of old growth that covers

that range of mountains. From a scenic standpoint, the Dacks are

very appealing, probably the most scenic range in the Northeast,

although prime supporters of New Hampshire's White Mountains might

argue that point. From your past posts and description of interests,

you will definitely enjoy the Dacks.

Could there be a counterpart movement in the South to that which led

to the Dacks? I think the chances of that are zero.

Bob

==============================================================================

TOPIC: Adirondack High Peaks

http://groups.google.com/group/entstrees/browse_thread/thread/8603682b7dd767b9?hl=en

==============================================================================

== 1 of 3 ==

Date: Tues, Aug 19 2008 3:50 am

From: JamesRobertSmith

> Could there be a counterpart movement in the South to that

which led to the Dacks? I think the chances of that are zero.

Unfortunately, true.

I used to wonder why the Dacks looked so different from the rest of

the eastern ranges. I finally read that there's ongoing uplifting

occurring in the Adirondacks and that, coupled with the glaciation

that swept through, makes them look so much more rugged than the

various Appalachian ranges with which they are often compared. I've

been to the Whites in New Hampshire (climbed Mount Washington via

Tuckerman's Ravine) and the Longfellows in Maine (climbed Katahdin

via

Cathedral Trail, Knife's Edge, Helon Taylor Trail). Those are

probably

the most spectacular peaks I've hiked in the east. But I can see

where

the high peaks of the Dacks could at least equal them, if not

surpass

them for grandeur from the photos I've seen.

== 2 of 3 ==

Date: Tues, Aug 19 2008 5:54 am

From: dbhguru@comcast.net

James,

The High Peaks are comparable to the Whites in ruggedness. The

tallest of the peaks in the Dacks in terms of the rise from base to

summit is Giant Mountain, which rises 4,000 feet above its eastern

base.

The 4,000-ft base to summit threshold is a tough one to beat in the

East. Kathadin makes it, Giant Mountain makes it, several of the

peaks of the Presidential Range make it, a couple of points in the

Blacks make it (or almost), and several peaks in the Smokies make

it. Leconte in the Smokies is usually considered to have the highest

base to summit rise. Some sources list the base as some spot in

Gatlinburg, giving Leconte a 5,301-foot rise.

Bob

== 3 of 3 ==

Date: Tues, Aug 19 2008 5:52 pm

From: JamesRobertSmith

Yes, on the LeConte figure. I did the only vertical mile hike in the

East. You start at the Gatlinburg city limits, hike the Gatlinburg

Trail to near the visitors center, then cross over and take the

Sugarlands Trail and from there you can take several combinations. I

did it in March 2005. A long day. The temperatures were in the

mid-50s

in Gatlinburg, but sub-freezing on the summit of LeConte with over

17"

of brand new snow on the top. We hiked through some short flurries

on

the way up, but missed the big snowstorm from the previous evening.

That one remains one of my all-time favorite hiking experiences.

There are some other combinations to the summit of LeConte to do a

vertical mile. You can also hike up Cherokee Orchard Road to the

several trailheads to the top, including Rainbow Falls, Bullhead,

etc.

JRS.

==============================================================================

TOPIC: Adirondack High Peaks

http://groups.google.com/group/entstrees/browse_thread/thread/8603682b7dd767b9?hl=en

==============================================================================

== 1 of 1 ==

Date: Tues, Aug 19 2008 7:38 pm

From: DON BERTOLETTE

James (does anybody call you JimBob, and get away with it?)-

I remember just about every vertical mile I ever did (some that are

still little more than a blur of pain!). The most recent was the

most odd for me, and took place in 2005. May have been my last too,

having crossed my 60th this summer. The odd thing was that it

started on the South Rim, and dropped (precipitously at times) very

close to a mile before reaching the Colorado River, only to have to

climb back UP to that same rim. All but one other of my 'vertical

miles' occurred with the grueling part first, and a nearly leisurely

walk back down.

The other? That was 35 years ago, dropping a vertical mile from 9400

foot Spanish Meadow (Sierra Nevada) to Tehipite Canyon (aka Little

Yosemite Valley) on the North Fork of the Kings River Canyon, WITHIN

A HORIZONTAL MILE (actually within a USGS Topo Section

square...:>) Subalpine fir down through several vegetation zones

into Yucca and Sage in sandy flats 'owned' by rattlesnakes, along

the Kings River. One of those hikes that served as source for many

stories!

-DonRB

|